Isoniazid

Andrew Ian Stolbach, M.D., M.P.H.

- Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/profiles/results/directory/profile/0022077/andrew-stolbach

Alterations in the physiological important to note that not all persistent pain is neu function of pain pathways as a result of tissue dam ropathic symptoms after miscarriage cheap isoniazid 300 mg overnight delivery. The pharmacological threshold and silent nociceptors are activated by a treatment of acute pain must be aggressive treatment viral conjunctivitis safe 300mg isoniazid, multi decrease in their threshold and show an increase in modal and preemptive to reduce the likelihood of the responsiveness (peripheral sensitization) treatment 2 degree burns buy generic isoniazid online. Similarly symptoms 9 days after embryo transfer purchase generic isoniazid from india, pain gesic and stepwise increase the potency of the med transmission is facilitated and inhibitory influences ication until pain relief is felt. Disinhibition is the disturbance of this bal ications because they enhance the central effect of ance with relief from inhibitory neuronal mecha analgesics and target associated depression, fear nisms. Non-pharmacological treatments of cial factors have a significant influence on the mod chronic back pain such as back school, exercise ther ulation of the afferent sensory input. Areport by the Ameri can Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Pain Management, Chronic Pain Section. Anonymous (2004) Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative set ting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Goubert L, Crombez G, De Bourdeaudhuij I (2004) Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: prevalence and interrelationships. Schofferman J (1999) Long-term opioid analgesic therapy for severe refractory lumbar spine pain. The baseline idea of epidemiology is that disease and the association between causal factors are not distributed at random in human populations. A second significant goal of epidemiology therefore is to rule out alternative sources of association. Prevalence refers to the percentage of a population that is affected withaparticulardiseaseatagiventimeorforagivenperiod. Frequentlyused time periods are the whole adult lifetime until the establishing diagnosis (life 154 Section Basic Science time prevalence), or 1, 6, or 12 months before the interview-establishing diagno sis (1-, 6-, or 12-month prevalence rates; also called current prevalence rates). Point prevalence indicates the percentage of those reporting pain on the day of the interview. Incidence refers to the number or rate of new cases of the disorder per persons at risk (usually 100 or 1000) during a specified period of time (usually one year). From this definition it follows that incidence rates are hard to estimate when conditions are widespread or often reoccur and therefore lack clear information on first onset. Persistence and recurrence are also captured by measuring the totalnumberofdayswithpaininthelastyear. For instance it was shown recently that identify risk factors, different definitions of back pain are systematically related to differences in prev predict natural history alence rates [68]. Itis not easy to differentiate between specific and non-specific spinal disorders by early symptoms, because the primary manifestation of most spinal disorders is pain involving the neck and back. For pain which is not radiating into the extremities the term axial pain is often used. Symptoms are classified as subacute if they most common symptoms in occur after a prolonged period (6 months) without pain and with a retrospective non-specific spinal disorders duration of less than 3 months. Back and neck pain within non-specific spinal disorders are frequently accompanied by other types of musculoskeletal pain, bodily complaints, psychological distress and, especially in chronic cases, amplified dysfunctional cognition. It radiates down the leg accord ing to the dermatone and is accompanied by numbness or tingling and mus cle weakness. Most epidemiological studies do not differentiate the lifetime prevalence between types of pain [66]. Pengel and colleagues showed that 73% of patients had at least one recurrence within 12 months [71]. Thereafter levels for Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Spinal Disorders Chapter 6 157 pain, and disability, and return to work remain almost constant [71]. There is increasing evidence that non-specific back pain in adults shows a fluctuating, recurrent and intermittent course that may ultimately lead to a chronic phase [19]. Neck Pain Neck pain located by a mannequin drawing is most often defined as pain occur ring in the area from the occiput to the third thoracic vertebra [21, 22]. Recently Fejer and coworkers showed in their review of 56 epidemiological studiesthatneckpainiscommoninmanyareasoftheworldandnumbersdid not differ systematically with most definitions of neck pain. Numbers did not differ systematically depending on whether the shoulder region was included or not, nor was the quality of studies systematically related to prevalence rates. It was first specifi disorders may result from cally defined as an acceleration-deceleration injury (usually related to accidents cervical sprain (frequently in vehicles), but later on the term whiplash syndrome was adopted for all types of rear-end collision) neck injuries [66]; nonetheless, the causal link to trauma is not well documented. Pain, Impairment and Disability Impairment defines an abnormality in structure or functioning of the body that may include pain, and disability defines the reduction in the performance of activities. Because in non-specific spinal disorders the etiology is uncertain, the establishment of impairment in these disorders is often less clear-cut than that of 158 Section Basic Science 100 23. It Pain and disability is also important to make a distinction between pain and disability. Painanddis must be differentiated ability differ in their risk factors, prevalence and incidence, and they have devel oped very differently in their prevalence rates over time. In Germany and some other countries, however, the trend for an increase in absence days in recent decades has stopped and numbers seem to have leveled off [94]. Risk factors and obstacles the Glasgow Illness Model is an operational clinical model of low back disabil to recovery potentially can ity [99, 104] that includes physical, psychological, and social elements (Fig. It differ for pain and disability assumes that most back and neck pain starts with a physical problem, which causes nociception, at least initially. Psychological distress may significantly amplify the subjective pain experience and lead to abnormal illness behavior. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Spinal Disorders Chapter 6 159 Sick role Illness behavior Distress Figure 2 Physical Glasgow Illness Model of Disability [99]. This operational model of Problem lowbackdisability describesthedevelopment from aphysical prob lem causing nociception to illness behavior and an alteration of the social role. A small minority of patients persist in the sick role, expe riencing high levels of pain, even though the initial cause of nociception should have ceased and healing should have occurred. Furthermore, muscu families, and society loskeletal complaints are among the leading causes of long-term disability [94, 102]. As such, non-specific back pain is often accompanied by psychological distress (depression or anxiety), impaired cognition and dysfunctional pain behavior. In that case, all relevant outcomes and costs are measured, regardless of who is responsible for the costs and who benefits from the effects. Since spinal disorders result in high costs to society, there have been an increasing number of economic evaluations. The economic burden of spinal disorders includes: direct, indirect, and intangible costs Direct costs concern medical expenditure, such as the cost of prevention, detec tion, treatment, rehabilitation, and long-term care. Estimates of direct and indirect annual costs of musculoskeletal disorders add up to approximately 24. Par ticipants in this study rated their loss in productivity due to musculoskeletal problems in the last month compared with the previous month.

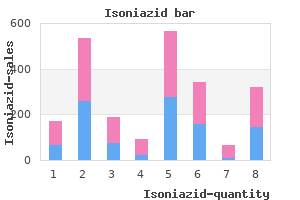

This was individually adminis problems with the words themselves might have contri tered in a quiet room in Cambridge or Exeter medicine zanaflex generic isoniazid 300 mg with visa. They Percentage of Subjects in Groups 2 and 3 Combined medicine overdose buy isoniazid 300mg free shipping, Who were then encouraged to read these particular meanings and Chose Each Word on Each Item were told that they could return to this glossary at any point during the testing treatment trends purchase 300 mg isoniazid with amex. Item Target Foil 1 Foil 2 Foil 3 1 31n6 1n8 26n2 40n4 Eyes Test Development 2 53n1 4n0 5n8 37n1 3 78n7 4n9 12n0 4n4 Target words and foils were generated by the rst two authors 4 82n1 5n4 4n9 7n6 and were then piloted on groups of eight judges (four male medications known to cause pill-induced esophagitis proven 300 mg isoniazid, four 5 84n9 4n0 2n2 8n9 female). The criterion adopted was that at least ve out of eight 6 79n6 1n3 8n0 11n1 judges agreed that the target word was the most suitable 7 79n9 7n6 10n3 2n2 description for each stimulus and that no more than two judges 8 79n5 3n6 13n8 3n1 picked any single foil. Items that failed to meet this criterion had 9 72n9 6n7 14n7 5n8 new target words, foils, or both generated and were then re 10 74n7 12n9 8n9 3n6 piloted with successive groups of judges until the criterion was 11 83n6 4n9 8n9 2n7 met for all items. New criteria were applied to these data: at least 50% of 16 72n9 7n1 4n0 16n0 subjects had to select the target word and no more than 25% 17 86n7 6n2 5n3 1n8 could select any one of the foils. These criteria were arbitrarily 18 76n0 1n8 13n3 8n9 selected but with the aim of checking that a clear majority of the 19 79n6 9n3 4n0 7n1 normal controls selected the target word and that this was 20 63n4 18n8 16n1 1n8 selected at least twice as often as any foil. Items 1, 2, 12 and 40 21 68n3 10n3 4n5 17n0 failed to meet these criteria and were therefore dropped. Thus 23 88n0 5n3 6n7 0n0 target words were established on the basis of consensus from a 24 77n3 12n4 8n9 1n3 large population, since there is no objective method for 25 84n9 1n3 3n6 10n2 identifying the underlying mental state from an expression. The 26 80n9 0n4 4n0 14n7 complete list of target mental state words (in italic) and their 27 75n6 8n0 4n0 12n4 foils are shown in Appendix A. Normal adults were found to be at ceiling on the gender recognition task during Results piloting so, to save time, were not required to do this task. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations on than males, whilst the interaction was insigni cant, the Revised Eyes Task for each of the four groups, and F(1, 224) l 0n79, p ln376. There were no within-group di erences in Group 3 of group, F(3, 250) l 17n87, p ln0001. The sex di erence approached signi cance, Groups 3 and 4, for which there was no di erence. This therefore validates it as a and Eyes Test were, as expected, inversely correlated useful test with which to identify subtle impairments in (r lkn53, p ln004). This was true for all three groups social intelligence in otherwise normally intelligent adults. The Revised Eyes Test may be relevant to clinical groups beyond those on the autistic spectrum. The test Discussion has recently been used with these groups (Stone, Baron this study reports normative data on the Revised Eyes Cohen, & Knight, 1999; Stone, Baron-Cohen, Young, & Test for adults. We have recently developed a child version render this test a more sensitive measure of adult social of this test, reported separately (Baron-Cohen, Wheel intelligence. As was hoped, the modi cations from the wright, Spong, Scahill, & Lawson, in press). This is important if the test is to do activity in the normal (but not in the autistic) brain more than discriminate extreme performance and instead (Baron-Cohen, Ring, et al. The cognitive basis of processing approaches may be a fruitful way to explore a biological disorder: Autism. Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger Manuscript accepted 30 June 2000 248 S. The views expressed are the independent products of university research and do not necessarily represent the views of the Iowa Department of Human Services or the University of Iowa. Due to the difficulty in finding interventions that work and that are readily available regardless of geographic location or financial resources, the field has nurtured many popular interventions that lack support from scientific research. At the same time, each child or adult with autism is unique, and some of the research strategies that have formed the foundation of traditional treatment research (such as randomized controlled trials) have been difficult to complete with large samples of participants with autism. For this reason, the interventions reviewed in this summary were evaluated in relation to several accepted standards of scientific quality and included both randomized group studies and carefully controlled single-subject research designs. The views expressed in this summary are the independent products of university research and do not necessarily represent the views of the Iowa Department of Human Services or the University of Iowa. These conditions share many of the same behaviors, but they differ in terms of when the behaviors start, how severe they are, and the precise pattern of problems. As many as 60 75% of children with Autistic Disorder also have intellectual disabilities, but some children with Autistic Disorder can develop average or even superior intellectual abilities. Even in children with intellectual disabilities, there may be isolated skills that are highly developed (such as in music, math, or memory). Children with Asperger Syndrome do not show general impairments in language or overall cognitive development, although impairments in visual-motor skills and pragmatic (social) language are common. Other Pervasive Developmental Disorders the essential feature of Childhood Disintegrative Disorder is a marked regression in multiple areas of functioning following a period of at least 2 years of apparently normal development. After the first 2 years of life (but before age 10), the child shows a clinically significant loss of previously acquired skills in at least two of the following areas: expressive or receptive language, social skills or adaptive behavior, bowel or bladder control, play, or motor skills. Between 5 and 48 months of age, the child with Rett Syndrome shows a slowing of head growth, loss of previously acquired purposeful hand skills, the development of stereotyped hand movements. Causes of Autism No one knows for sure what causes autism, but scientists believe that both genes and the environment play a role. Among identical twins, if one child has autism, then the other is likely to be affected 75-90% of the time. Some parents worry that vaccines cause autism, but the scientific evidence does not support this theory. There is some evidence that exposure to factors in the environment (such as viruses or infections) may play a role in causing some forms of autism. Prevalence In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported data on autism prevalence that concluded that the prevalence of autism had risen to 1 in every 110 American children, with rates of 1 in every 70 boys and 1 in every 315 girls. Lifetime Costs the Autism Society of America estimates that the lifetime cost of caring for a child with an autism spectrum disorder ranges from $3. Based on these estimates, the United States is facing almost $90 billion annually in costs for autism spectrum disorders. These costs include research, insurance costs and non-covered expenses, Medicaid waivers for autism, educational spending, housing, transportation, employment, therapeutic services, and caregiver costs. There are no specific medical tests for diagnosing autism although there are genetic tests for some disorders that may be associated with behaviors on the autism spectrum. In addition to assessing the key symptoms of autism, a review of sleep, feeding, coordination problems, and sensory sensitivities is often recommended. Medical factors that may be causing pain or irritability should be recognized and treated whenever possible. A metabolic workup and genetic testing for syndromes with autism-like features. Consultation with specialists may be necessary to assess for neurological (neurologist), genetic (clinical geneticist), gastrointestinal (gastroenterology), speech (speech/language pathologist), or motor concerns (physical or occupational therapist).

Order genuine isoniazid line. இந்த அறிகுறிகள் உங்கள் உடலில் உள்ளதா- symptoms in body.

Adam also showed an increase in social interactions such as greeting the researchers and other teachers such as the librarian symptoms of kidney stones discount isoniazid 300mg overnight delivery. However medications listed alphabetically buy 300mg isoniazid otc, the latter study showed limited generalization and maintenance of social behavior medicine 003 buy isoniazid 300 mg low cost, presumably due to the length of the intervention period 400 medications isoniazid 300mg sale. According to the data noted in the journal, Adam was capable of working cooperatively with his peers. During two of the sessions, Adam was required to stand and present what he has done in front of his classmates. However, it should be noted that he was not capable of expressing himself in a fluent way. The teachers usually gave him probes or asked him specific questions in order for him to express himself orally. When comparing Adam to the peers in his group, it was noticeable that he still has not reached their level of oral expression. The researchers also noted that, apparently, the other students in class knew that Adam is somewhat different. They attempted to assist him by asking if he needed help or by guiding him in what he should do on occasions. For example, the teacher called Adam while he was working on a given task, so one of his group members came up to him and told him that the teacher was calling him; his peer then told him he should see what she wants. Both children were placed in groups which included three typically developing peers, one maleand two females. According to the results of their study, the group work substantially increased the level of social engagement for both children. The two children with autism were 8 and 9-year-old boys; they were high functioning in terms oflanguage and intellectual abilities but lacked social competence. The group sessions resulted inan increase in interaction from 80 to 120 seconds per 5-minute sample for the children with autism. Additionally there was an increase in themean interaction time of peers, and the children with autism displayed improved academic achievement (DiSalvo& Oswald, 2002). These children had adequate language skills and couldread at the kindergarten level, but suffered from weak social competence. The results indicated that the childrenwith autism increased their social interaction by 36% and 38% respectively during the treatmentphase, as compared with thebaseline phase, in which children attended regular classes but were not assigned a buddy (Disalvo& Oswald, 2002). Secondly, positive change was documented in the scores of the teachers and special educator on the rating scales; these changes were related to the skills targeted through the social stories. However, it should be noted that, although change was evident, most of his scores remained in the elevated range. It seems as though Adam enjoyed the social story session since he asked to go to the library on several different occasions. Peer mediated intervention, through cooperative group work also seemed to be an enjoyable activity for Adam and his peers. Peer mediated intervention also appeared to be beneficial in this particular case because it gave Adam the opportunity to practice what he was taught natural settings (versus un-natural settings such as the library). First, the study was implemented on one student, thus limited generalization can be made. Thirdly, the observation was conducted by the researchers, which might have created internal bias. Moreover, we cannot say with certainty that Adam will maintain his pro-social behavior since additional post-testing after longer periods was not conducted. This combined intervention was found to be enjoyable and effective with a first grader, however it might not be as effective for older students and adolescents. Additionally, the cooperative group work not only encourages the integration of children with special needs with their regular peers, it also reinforces desirable behavior and provides the student with several opportunities to apply what was taught in the social stories. Some of these components are the following: (a) use social stories that describe specific situations and expected responses (refer to Gray, (1994)); (b) provide the reader with insight on how others would feel when they he/she acts in an appropriate way; (c) model the appropriate behavior expected of the child; (d) provide the child with ample opportunities to practice what was taught in the story. This can be done by involving peers through cooperative group work or involving the parents; (e) use positive reinforcement to encourage the reoccurrence of desired behaviors. Future studies should try to identify which elements in the combined intervention lead to the greatest change in behavior; they should also identify the appropriate time needed for the intervention to be effective. Perhaps future studies can extend the length of treatment or intensify the intervention by giving the child additional afterschool sessions. Additionally, more research should be conducted in order to address the issue of maintenance and generalization of social skills. Perhaps future studies can conduct post tests after longer periods of time from discontinuing the intervention in order to see the long term effect of the combined intervention. Social story intervention: Improving communication skills in a child with an autism spectrum disorder. A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Examining the effectiveness of an outpatient clinic-based social skills group for high functioning children with autism. The social, behavioral, and academic experiences of children with Asperger Syndrome. Reciprocal social behavior in children with and without pervasive developmental disorders. Social Skills Interventions for Students With Asperger Syndrome and High Functioning Autism: Research Findings and Implications for Teachers. Peer-mediated interventions to increase the social interaction of children with autism: Consideration of peer expectancies. Class wide peer tutoring: An integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism and general education peers. Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Children and youth with asperger syndrome strategies for success in inclusive settings. Lego therapy and the social use of language programme: An evaluation of two social skills interventions for children with high functioning autism and asperger syndrome. Using Social stories to improve the social behavior of children with asperger syndrome. Evaluating educational interventions: Single-case designs for measuring response to intervention. Simulating social interaction to address deficits of autistic spectrum disorder in children. Social skills training for adolescents with asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. The aim is to check how much intensive sex education could replace problem sexual behaviours by new behaviours that enhance social adaptation. The following topics will be addressed: (1) Puberty and sexual development; (2) Friendship: personal values, personality and interpreting different messages; (3) Emotions: "Mind Reading" software, how to read emotions of the face, emotions related to sexuality; (4) Communication: verbal and nonverbal, Theory of Mind, role-playing; (5) Sexual behaviour: enhancing appropriate behaviours, hyper and hyposensitivity of the body; (6) Intimacy:, misinterpretations, limits; and (7) Interpersonal relationships in different contexts: school, work, friends, couples. In addition, several parents and professionals feel uncomfortable talking about sexuality. Nonetheless, sexuality is an integral part of the normal development of adolescents and we have recently begun to recognize that individuals have the right to experience and fulfill this important part of their life. Clearly, this is an opportune and appropriate time in which to provide them with sexual education. In addition to going through the same stages of sexual development (increase in hormones, body hair, genital maturation, etc. They differ in that they experience major difficulties with communication and social interaction which directly impair their ability to interact sexually as well as reinforce the emergence of inappropriate sexual behaviors. When the topic of sexuality has been addressed in the literature, it has usually been restricted to a discussion of problem behaviors. Such a perspective is limited in that it fails to consider the complexity of sexuality in general. In contrast, parents and professionals often view sexuality in a much different manner.

Using the principles of motor learning de scribed above medications that cause dry mouth purchase isoniazid 300mg without prescription, the task is to overload impaired muscle groups during functional tasks and then allow them time to recover to achieve best outcomes symptoms 2 weeks after conception order isoniazid 300 mg on-line. When looking at general exercise principles suitable for an ageing population Abernethy et al medications heart disease purchase isoniazid without prescription. Due to the effects of ageing medications you can give your cat order isoniazid 300mg free shipping, clinicians should expect slower progress and improvement in exercise capacity. Note also that strength training is contraindicated for certain populations; namely motor-neuron disease and multiple sclerosis. In these conditions strength training is not bene cial and may even be harmful (Clark, 2003). Muscle weakness Weakness on the other hand is a reduction in force and the concept of fatigue is closely associated with it (Clark, 2003). However it is very dif cult to predict the degree of functional limitation from the severity of weakness observed. Disuse atrophy speci cally of the superior constrictors has been postulated by Perlman et al. For example, anterior and superior movement of the larynx during swallowing occurs as a result of contraction of the anterior belly of the digastric, posterior belly of the digastric, geniohyoid, omohyoid, stylohyoid and mylohyoid muscles (Moore and Dalley, 1999). This is where the muscle is activated but the overall length of the muscle-tendon complex does not change. Thus isometric contractions are important for stabilization and maintenance of posture. While the study is very detailed, it does not take into account the chang ing roles of the muscle complexes required for swallowing. It also cannot simulate the actions required for swallowing any bolus, let alone boluses of different textures and viscosities. The study treats the muscles required for swallowing as one might view a set of musical scales for the piano. Each note is included in the scale, but it is the organization of those notes in a particular order at a particular time that forms a so nata. Similarly it is the organization of a particular set of muscles in a particular order at a particular time that determines the act of swallowing rather than a record of indi vidual muscle actions engaged in one activity (concentric movement) in isolation. Many clinicians continue to use oral motor exercises under the misguided belief that these movements will improve general muscle strength and thence improve mus cle function during speech and swallowing. Oral motor exercises typically include tongue protrusion, lateralization, and elevation; and pursing and spreading of the lips in a drill-like fashion. First and foremost, there is insuf cient evidence to sup port the use of oral motor exercises to improve swallowing function (Langmore and Miller, 1994; Clark, 2003; Reilly, 2004). Literature that is reported for oral motor exercises often (a) lacks control groups, (b) provides results from single case studies or small numbers of subjects and (c) often combines the approach with other thera pies, negating a case for its use in isolation. The aforementioned notes on speci city of motor task should also indicate that drill exercises of the oral musculature are of dubious value. Based on the lack of evidence for oral motor exercises and the lack of theoretical underpinnings for their use in dysphagia rehabilitation, oral motor exercises are not recommended for rehabilita tion of swallowing. However, active range of movement exercises may be bene cial in preventing the formation of restrictive scar tissue (Clark, 2003). This is particu larly relevant in the head and neck population where the formation of scar tissue following surgery or chemo and/or radiotherapy is an issue. For exam ple, based on assessment results the clinician may work on (a) aspects of the oral phase, (b) aspects of the pharyngeal phase, (c) both aspects of swallowing function, (d) swallow-respiratory coordination, or (e) removing the bolus from the oral cavity or pharynx. The non-oral patient presents as a special case in point, and this will be discussed separately. Traditionally therapeutic tasks such as oral motor exercises (discussed above) or swallowing manoeuvres are discussed under separate headings. In the following discussions, they will be included where they are applicable under the general headings below. Gentle repetitive pressure of the cup or spoon on the lower lip may also enhance lip and then jaw opening. Wherever possible, if the individual can self feed, this may also be a positive motivating factor in getting the bolus into the oral cavity. Collaborative work with an occupational therapist is recommended where self-feeding is one of the goals of treatment. Where there is spasticity in the muscles of the face it may be appropriate to use massage to reduce the tone to allow the jaw to open (Clark, 2003). Verbal instruction to open the mouth should also accompany any assistive actions by the therapist. Taking the bolus from a cup, spoon or fork Taking the bolus from a cup, spoon or fork requires lip closure around the device. The task can be graded such that the clinician may move from large spoons to smaller spoons to allow the individual to increase amount of lip closure. Similarly progres sion from a medicine style cup (30ml capacity) to increasingly larger capacity cups may assist with the process of lip closure around a cup. Physical assistance to bring the cup or spoon to the mouth could be offered and then phased out as the individual becomes more independent with the task. Note that there will be considerably more closure required to use a spout cup or a straw. Lip closure to contain the bolus Lip closure to contain the bolus within the oral cavity requires that the lips come together with suf cient strength and tone. Where there is severely limited volitional movement, the clinician could manually assist the patient by closing the lips for them. Where there is volitional movement and suf cient cognitive capacity, the cli nician could also use a lollipop placed within the oral cavity and ask the individual to close their lips around it to encourage lip closure. Alternatively the clinician could use tethered shapes made out of acrylic or Te on as these will not deform within the oral cavity. The clinician could also try and remove the lollipop from the oral cavity while the patient resists this movement using lip closure to include resistance exer cise into the task. Lifesavers (candy) anchored using string (Huckabee and Pelletier, 1999) or dental oss have also been suggested for this manoeuvre; however, the clini cian needs to be mindful of melting the Lifesaver with exposure to saliva and likely sucking actions and thinning of the material allowing it to break, and lose the tether. Aspiration of bacterial pathogens in saliva is associated with an increased risk of developing aspiration pneumonia where dysphagia is also present (Langmore et al. Other methods of promoting lip closure include holding a straw or tongue depres sor with the lips and gradually increasing the length of time the individual holds the item between their lips to improve endurance (Sheppard, 2005). The clinician could attempt to remove the straw or tongue depressor while the patient grips it with their lips. The clinician could also ask the patient to press down rmly on the tongue depressor using their lips, repeating the motion until fatigued. The clinician could also ask the patient to use their lips (protrusion and retraction activities) to pull a strip of moistened gauze into the mouth (Huckabee and Pelletier, 1999). Note that these tasks aim at keep ing the bolus within the oral cavity and attempt to minimize drooling the material (liquid, solid or saliva) from the oral cavity. Manipulation of a solid bolus for deformation Manipulation of the solid bolus for effective deformation requires tongue agility, buccinator tone and lip and jaw closure. Individuals could be given large items to manipulate such as large pieces of gauze or lengths of liquorice (Logemann, 1998). Following this they could be asked to move the bolus to either side of the mouth and position it between the teeth or place it into the buccal cavities and then retrieve it from these posi tions.