Voveran sr

Howard Mark Lederman, M.D., Ph.D.

- Director, Immunodeficiency Clinic

- Professor of Pediatrics

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/profiles/results/directory/profile/0000112/howard-lederman

Dosimetric advantages of proton therapy over conventional radiotherapy with photons in young patients and adults with low-grade glioma muscle relaxant herniated disc discount 100mg voveran sr mastercard. Hata M muscle relaxant hiccups purchase voveran sr 100mg with visa, Miyanaga N spasms upper right abdomen voveran sr 100mg on-line, Tokuuye K spasmus nutans treatment purchase genuine voveran sr, Saida Y, Ohara K, Sugahara S, Kagei K, Igaki H, Hashimoto T, Hattori K, Shimazui T, Akaza H, Akine Y Proton beam therapy for invasive bladder cancer: a prospective study of bladder preserving therapy with combined radiotherapy and intra-arterial chemotherapy. A multidisciplinary orbit-sparing treatment approach that includes proton therapy for epithelial tumors of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Proton radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: a review of the clinical experience to date. Proton therapy reduces treatment-related toxicities for patients with nasopharyngeal cancer: a case-match control study of intensity-modulated proton therapy and intensity modulated photon therapy. A Phase ½ and biomarker study of preoperative short course chemoradiation with proton beam therapy and capecitabine followed by early surgery for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proton therapy with concurrent chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: technique and early results. Proton therapy patterns-of-care and early outcomes for Hodgkin lymphoma: results from the Proton Collaborative Group Registry. Comparison of passive-beam proton therapy, helical tomotherapy and 3D conformal radiation therapy in Hodgkin’s lymphoma female patients receiving involved-field or involved site radiation therapy. Second cancer risk and mortality in men treated with radiotherapy for stage I seminoma. Comparing the dosimetric impact of interfractional anatomical changes in photon, proton and carbon ion radiotherapy for pancreatic cancer patients. Favourable long-term outcomes with brachytherapy-based regimens in men ≤60 years with clinically localized prostate cancer. Clinical outcomes of high-dose-rate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy in the management of clinically localized prostate cancer. Bayesian adaptive randomization trial of passive scattering proton therapy and intensity-modulated photon radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Initial Report of Pencil Beam Scanning Proton Therapy for Posthysterectomy Patients With Gynecologic Cancer. Fractionated proton radiation treatment for pediatric craniopharyngioma: preliminary report. Proton therapy for breast cancer after mastectomy: early outcomes of a prospective clinical trial. Comparison of proton beam radiotherapy and hyper-fractionated accelerated chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Comparison of adverse effects of proton and x-ray chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer using an adaptive dose-volume histogram analysis. Which technique for radiation is most beneficial for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer? Intensity modulated proton therapy versus intensity modulated photon treatment, helical tomotherapy and volumetric arc therapy for primary radiation – an intraindividual comparison. Doses to head and neck normal tissues for early stage Hodgkin lymphoma after involved node radiotherapy. Reirradiation of recurrent and second primary head and neck cancer with proton therapy. Five-year outcomes from 3 prospective trials of image-guided proton therapy for prostate cancer. Comparison of whole-body phantom designs to estimate organ equivalent neutron doses for secondary cancer risk assessment in proton therapy. Proton therapy with concomitant capecitabine for pancreatic and ampullary cancers is associated with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal toxicity. One hundred patients irradiated by a 3D conformal technique combining photon and proton beams. Pencil-beam scanning proton therapy for anal cancer: a dosimetric comparison with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Charged particle therapy versus photon therapy for paranasal sinus and nasal cavity malignant diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical evidence of variable proton biological effectiveness in pediatric patients treated for ependymoma. Will There Be a Clinically Significant Role for Protons in Patients With Gastrointestinal Malignancies? Proton beam radiation therapy results in significantly reduced toxicity compared with intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck tumors that require ipsilateral radiation. Long-term outcomes after proton beam therapy for sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Proton therapy and concomitant capecitabine for non-metastatic unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Predicted rates of secondary malignancies from proton versus photon radiation therapy for stage I seminoma. Intensity modulated proton therapy versus intensity modulated photon radiation therapy for oropharyngeal cancer: first comparative results of patient-reported outcomes. Long-term survival and toxicity in patients treated with high-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Upper gastrointestinal complications associated with gemcitabine concurrent proton radiotherapy for inoperable pancreatic cancer. Long-term single-institute experience with trimodal bladder-preserving therapy with proton beam therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. A dosimetric comparison of proton and photon therapy in unresectable cancers of the head of pancreas. Second cancers among 40,576 testicular cancer patients: focus on long-term survivors. Interfractional variations in the setup of pelvic bony anatomy and soft tissue, and their implications on the delivery of proton therapy for localized prostate cancer. Beam configuration selection for robust intensity-modulated proton therapy in cervical cancer using Pareto front comparison. Proton beam radiotherapy as part of comprehensive regional nodal irradiation for locally advanced breast cancer. Quality of life and patient-reported outcomes following proton radiation therapy: a systematic review. Prospective study of patient-reported symptom burden in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing proton or photon chemoradiation therapy. A pilot feasibility study of definitive concurrent chemoradiation with pencil beam scanning proton beam in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-c for carcinoma of the anal canal. Irradiation with protons for the individualized treatment of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Comparative outcomes after definitive chemoradiotherapy using proton beam therapy versus intensity modulated radiation therapy for esophageal cancer: a retrospective, single institutional analysis. Risk of developing second cancer from neutron dose in proton therapy as function of field characteristics, organ, and patient age. Secondary cancers after intensity-modulated radiotherapy, brachytherapy and radical prostatectomy for the treatment of prostate cancer: incidence and cause-specific survival outcomes according to the initial treatment intervention. Four-dimensional computed tomography-based treatment planning for intensity-modulated radiation therapy and proton therapy for distal esophageal cancer. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate: long-term results from Proton Radiation Oncology Group/American College of Radiology 95-09. Conventional external radiotherapy in the management of clivus chordomas with overt residual disease. The role of proton therapy in the treatment of large irradiation volumes: a comparative planning study of pancreatic and biliary tumors. In 1974, Nigro and colleagues from Wayne State reported their experience of 3 patients with anal carcinoma who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy and were found to have a complete response at the time of surgery. Several studies have evaluated various treatment regimens for the definitive care of patients with nonmetastatic squamous cell anal cancer. In an analysis of radiation planning quality, 81% of submitted cases required revision of planning following the initial submission secondary to incorrect contouring, noncompliance of normal tissue constraints, or incorrect target dosing. There is limited data on radiation therapy in the palliative treatment of anal cancer. Therefore, up to 10 fractions is recommended in the palliative treatment of anal cancer. In patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, radiation has been evaluated.

It is usually associated with damage to the non-dominant hemisphere spasms colon order generic voveran sr from india, and requires careful separation from aphasia and dysarthria muscle relaxant definition effective 100 mg voveran sr. Interventions such as syllable level therapy and metrical pacing have been studied and the use of computers to increase intensity of practice has been suggested spasms hindi meaning cheap 100mg voveran sr otc. Evidence to recommendations Studies in apraxia of speech are often small and the most recent Cochrane review (West et al zanaflex muscle relaxant 100mg voveran sr with amex, 2005) found no trials. There has been one recent crossover trial (Varley et al, 2016) which compared self-administered computerised communication therapy with a sham computerised treatment for people with chronic speech apraxia. Improvements in spoken word production (naming and repetition) were greater for the intervention group after the six week treatment but limited to trained single words. B People with severe communication difficulties but good cognitive and language function after stroke should be assessed and provided with alternative or augmentative communication techniques or aids to supplement or compensate for limited speech. Incontinence of urine greatly increases the risk of skin breakdown and pressure ulceration. Incontinence of faeces is associated with more severe stroke and is more difficult to manage. Constipation is common, occurring in 55% of people within the first month of stroke, and can compound urinary and faecal incontinence. Incontinence has a detrimental effect on mood, confidence, self-image and participation in rehabilitation and is associated with carer stress. Incontinence is an area of stroke that has received little research interest, despite its substantial negative impact. It needs to be managed proactively to allow people with stroke to fully participate in their own care and recovery both in the acute phase and beyond. Evidence to recommendations A 2013 review of bowel management strategies (Lim and Childs, 2013) identified three small studies of varying quality, and concluded that the evidence was limited but a structured nurse-led approach may be 67 effective. In a review of therapeutic education for people with stroke, Daviet et al (2012) concluded from small non-randomised studies that a nurse-targeted education programme may improve longer term continence. A small study by Guo et al (2014) examined the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of urinary incontinence over six months and found an improvement in nocturia, urgency and frequency. B People with stroke should not have an indwelling (urethral) catheter inserted unless indicated to relieve urinary retention or when fluid balance is critical. C People with stroke who have continued loss of bladder and/or bowel control 2 weeks after onset should be reassessed to identify the cause of incontinence, and be involved in deriving a treatment plan (with their family/carers if appropriate). The treatment plan should include: ‒ treatment of any identified cause of incontinence; ‒ training for the person with stroke and/or their family/carers in the management of incontinence; ‒ referral for specialist treatments and behavioural adaptations if the person is able to participate; ‒ adequate arrangements for the continued supply of continence aids and services. D People with stroke with continued loss of urinary continence should be offered behavioural interventions and adaptations such as: ‒ timed toileting; ‒ prompted voiding; ‒ review of caffeine intake; ‒ bladder retraining; ‒ pelvic floor exercises; ‒ external equipment prior to considering pharmaceutical and long-term catheter options. E People with stroke with constipation should be offered: ‒ advice on diet, fluid intake and exercise; ‒ a regulated routine of toileting; ‒ a prescribed drug review to minimise use of constipating drugs; ‒ oral laxatives; ‒ a structured bowel management programme which includes nurse-led bowel care interventions; ‒ education and information for the person with stroke and their family/carers; ‒ rectal laxatives if severe problems persist. F People with continued continence problems on transfer of care from hospital should receive follow-up with specialist continence services in the community. In a large survey of long-term stroke survivors half of the respondents reported fatigue and 43% of those with fatigue said they had not received the help they needed (McKevitt et al, 2011). The most common features of fatigue are a lack of energy or an increased need to rest every day, but fatigue is characteristically not relieved by rest. Both mental and physical activity can cause fatigue, and some people are affected more by one than the other. Many people with stroke have to make a greater effort to carry out their activities and this explanation can provide reassurance, as can the information that for many people fatigue decreases over time. Other factors associated with fatigue include side-effects of medication, disturbed sleep as a result of pain (Section 4. Fatigue can be assessed by the routine use of a structured assessment scales (Mead et al, 2007). Management strategies include the identification of triggers and re-energisers, environmental modifications and lifestyle changes, scheduling and pacing, cognitive strategies to reduce mental effort, and psychological support to address mood, stress and adjustment. Evidence to recommendations Recommendations are based on one Cochrane review of intervention trials (Wu et al, 2015), a systematic review of assessment measures (Mead et al, 2007) and Working Party consensus. Some pharmacological interventions (antidepressants or stimulants), psychological interventions and physical training are potential treatments but they require robust evaluation and there is insufficient evidence to recommend any specific intervention (Wu et al, 2015). Graded activity training and cognitive behavioural approaches such as activity scheduling have proved useful for non-stroke fatigue but their applicability to stroke is not known, and further research is needed. Future studies should assess fatigue systematically, provide treatment for a sufficient duration, follow up participants for sufficient time, and report adverse effects. The Cochrane review identified nine ongoing trials including three assessing fatigue as a secondary outcome. B People with fatigue after stroke and their family/carers should be given information, reassurance and support to identify their personal indicators and triggers for fatigue and supported to develop strategies to anticipate and manage fatigue. Malnutrition is associated with increased mortality and 69 complications, as well as poorer functional and clinical outcomes (Davalos et al, 1996, Yoo et al, 2008). Up to one quarter of stroke patients become more malnourished in the first weeks following stroke, and the risk of malnutrition increases with increasing hospital stay (Davalos et al, 1996, Yoo et al, 2008). Poor nutritional intake, weight loss, and feeding and swallowing problems can persist for many months (Finestone et al, 2002, Perry, 2004, Jonsson et al, 2008). Multiple factors may contribute to a high risk of dehydration and malnutrition after stroke including physical, social and psychological issues. In people requiring nasogastric tube feeding, delays in initiating feeding and frequent dislodgement can further affect nutritional status, although the use of nasal bridles may be helpful (Beavan et al, 2010). There is insufficient evidence to determine whether hand mittens prevent nasogastric tube dislodgement. The assessment of dehydration is complex, and when used in isolation many common assessment methods are inaccurate (Hooper et al, 2015). A Cochrane review by Hooper et al (2015) of the signs and symptoms of impending and current water loss dehydration in older people concluded that there is little evidence that any one symptom, sign or test, including many that clinicians customarily rely on, has any diagnostic utility for dehydration. A 2012 Cochrane review (Geeganage et al, 2012) included eight trials of the effectiveness of nutritional support in non-dysphagic acute and sub-acute stroke (less than six months). Although nutritional supplementation resulted in significantly reduced pressure sores, increased energy intake and increased protein intake, this did not affect length of hospital stay, dependency or mortality. Studies included people with variable baseline nutritional status, not just those who were malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. Since the last guideline, two Cochrane reviews have compared routes of enteral tube feeding. Although gastrostomy reduced intervention failure, there was no difference between the interventions in weight change, pneumonia or mortality. Most studies were small with considerable heterogeneity and methodological limitations. Although gastrostomy feeding was associated with fewer feeding failures, less gastrointestinal bleeding and fewer pressure sores, there was no significant difference in length of hospital stay, dependency or mortality. In a sample of 104 people, those who had a nasogastric tube secured using a nasal bridle received a higher proportion of prescribed feed and fluid compared to the control group who had tubes secured using standard practice. Mahoney et al (2015) identified the need for training and protocols in confirming the placement and securing of nasogastric tubes. B Patients with acute stroke should be screened for the risk of malnutrition on admission and at least weekly thereafter. C Patients with acute stroke who are adequately nourished on admission and are able to meet their nutritional needs orally should not routinely receive oral nutritional supplements. E Patients with stroke who are at risk of malnutrition should be offered nutritional support. This may include oral nutritional supplements, specialist dietary advice and/or tube feeding in accordance with their expressed wishes or, if the patient lacks mental capacity, in their best interests. F Patients with stroke who are unable to maintain adequate nutrition and fluids orally should be: ‒ referred to a dietitian for specialist nutritional assessment, advice and monitoring; ‒ be considered for nasogastric tube feeding within 24 hours of admission; ‒ assessed for a nasal bridle if the nasogastric tube needs frequent replacement, using locally agreed protocols; ‒ assessed for gastrostomy if they are unable to tolerate a nasogastric tube with nasal bridle. G People with stroke who require food or fluid of a modified consistency should: ‒ be referred to a dietitian for specialist nutritional assessment, advice and monitoring; ‒ have the texture of modified food or fluids prescribed using nationally agreed descriptors. H People with stroke should be considered for gastrostomy feeding if they: ‒ need but are unable to tolerate nasogastric tube feeding; ‒ are unable to swallow adequate food and fluids orally by four weeks from the onset of stroke; ‒ are at high long-term risk of malnutrition. I People with difficulties self-feeding after stroke should be assessed and provided with the appropriate equipment and assistance (including physical help and verbal encouragement) to promote independent and safe feeding.

All patients should be given written information regarding diagnostic tests to enable them to give informed consent muscle relaxant cheap 100mg voveran sr with mastercard. Newer drug therapies for non-small cell lung cancer work best if they are targeted on the basis of historical sub-type and/or predictive markers muscle relaxant otc cvs purchase generic voveran sr from india. Tissue samples of sufficient size and quality are therefore required to enable pathologists to classify non-small cell lung cancer into squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma wherever possible spasms synonyms order 100 mg voveran sr visa. In addition spasms stomach area buy voveran sr 100mg otc, further tests, requiring additional tissue or cells, may also be needed to detect specific markers that predict whether targeted treatments are likely to be effective, for example epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. As more targeted therapies become available it is likely that further tests will need to be performed to detect the relevant predictive markers. Also patients with adenocarcinoma who are being considered for surgery or radical treatment. Staging for Non-small cell lung cancer General approach Patients with lung cancer suitable for radical treatment or chemotherapy, or need radiotherapy or ablative treatment for relief of symptoms, should be treated without undue delay, according to the Welsh Assembly Government and Department of Health recommendations (within 31 days of the decision to treat and within 62 days of their urgent referral). Choose investigations that give the most information about diagnosis and staging with least risk to the patient. Think carefully before performing a test that gives only diagnostic pathology when information on staging is also needed to guide treatment. If patients with suspected lung cancer have an accessible pleural effusion, thoracocentesis is recommended under ultrasound guidance. If this is negative then image guided pleural biopsy is the next step 12 Ensure adequate samples are taken without unacceptable risk to the patient to permit pathological diagnosis including tumour subtyping and measurement of predictive markers. There should be access to molecular testing by an accredited laboratory for gene mutations. Pathologists should therefore handle samples sent for suspected lung cancer judiciously and endeavor to retain enough tissue for testing while making a diagnosis. A plain radiograph should be performed in the first instance for patients with localized signs or symptoms of bone metastasis. In cases where the patient is not considered fit to receive any form of radical treatment or palliative chemotherapy for advanced disease, the team may not consider it appropriate to seek more than a clinical diagnosis. It is good practice for patients to be seen by the diagnosing doctor and the specialist nurse after the multidisciplinary team meeting to discuss results and have an opportunity to consider treatment options. All members of the team who have contact with patients at this point in the pathway should have training in advanced communication skills. The details of the dataset can be found on the Health & Social Care Information Centre website at Details of the audit and the dataset requirements are available at the dataset homepage: Trusts are required to submit this data within 25 working days of the month in which patients were first seen for the 2ww target, or the month in which the patient was treated. However, the key-worker may be differing persons at various stages of the care trajectory. For example: a member of the chemotherapy team whilst undergoing chemotherapy, a patient entered into a clinical trial may have the research nurse as the key worker. All patients will be made aware of who their key-worker is and have the right to ask for another named clinician. The key-worker will provide written contact details including a telephone number for all the patients for whom they act as the key-worker. Smoking cessation in lung cancer More than 80% of deaths from lung cancer are attributable to smoking. This has an additional benefit where preoperative smoking cessation reduces the risk of complications from surgery. Others include radiotherapy, combined chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. There are many factors for the patient and healthcare professionals to consider when deciding if treatment with curative intent is appropriate. The most important factors are the likelihood of treatment achieving a cure and the fitness of the patient. The former is essentially about either the ability to clear the cancer surgically, with or without other modalities, or the ability to treat all the cancer with radiotherapy with curative intent. The latter has two components – the extent of risk to the patient in terms of mortality and the degree of morbidity (principally post operative dyspnea and quality of life. A patient whose fitness is borderline may not be able to tolerate a more extensive resection needed to achieve cure. Ultimately decisions about treatment are made by the patient following an informed discussion. Seek a cardiology review in patients with an active cardiac condition, or three or more risk factors, or poor cardiac functional capacity. Offer surgery without further investigations to patients with two or fewer risk factors and good cardiac functional capacity. Continue anti-ischaemic treatment in the perioperative period, including aspirin, statins and beta-blockers. If a patient has a coronary stent, discuss perioperative anti-platelet treatment with a cardiologist. Consider revascularisation (percutaneous intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting) before surgery for patients with chronic stable angina and conventional indications for revascularisation. Lung function Perform spirometry in all patients being considered for treatment with curative intent. When considering surgery perform a segment count to predict postoperative lung function. Consider using shuttle walk testing (using a distance walked of more than 400 m as a cut-off for good function) to assess fitness of patients with moderate to high risk of postoperative dyspnoea. Assessment before radiotherapy with curative intent 18 A clinical oncologist specialising in thoracic oncology should determine suitability for radiotherapy with curative intent, taking into account performance status and comorbidities. Segment counting is employed to predict post-operative lung function and therefore the risk of post-operative dyspnoea. Sub-lobar and broncho-angioplastic resections allow fewer segments to be removed and therefore can extend the boundaries of surgery. Lobectomy Lobectomy is indicated for carcinoma if the growth is relatively peripheral and confined to one lobe (or two in the case of middle and lower right. Pneumonectomy should include removal of carinal, paratracheal, pretracheal and paraoesophageal lymph nodes if they appear to be involved. Mortality for pneumonectomy is around 8%, but is much higher in those over 80, when a more limited resection could be considered. Extended (intrapericardial) Resection this involves the opening of the whole pericardium around the lung root with division of the pulmonary vessels within the mediastinum. It may be considered for very central tumours or those with mediastinal extension without N2 disease. Wedge resection involves resection of the tumour with a surrounding margin of normal lung tissue, and does not follow anatomical boundaries, whereas segmental resection involves the division of vessels and bronchi to a distinct anatomical segment(s). Segmental resection removes draining lymphatics and veins and intuitively might be expected to result in lower recurrence rates, although there is no evidence for this. Segmental resection may not always be technically feasible, and is best suited to the left upper lobe (lingula, apicoposterior and anterior segments) and the apical segment of both lower lobes. Broncho-angioplastic resections Bronchoplastic resections involve removing a portion of either the main bronchus or bronchus intermedius with a complete ring of airway followed by the re-anastomosis of proximal and distal airway. Angioplastic resections involve removing part of the main pulmonary artery followed by end-to-end anastomosis or reconstruction. However, there are no randomised trials and outcome measures are not as rigorous as for the trials of lung volume reduction in emphysema. Intraoperative nodal sampling There is considerable variation in the practice of lymph node sampling from lobe specific sampling to systematic nodal dissection. Surgery should be offered to patients who are medically fit and suitable for treatment with curative intent. Multiple wedge resections may be considered in patients with a limited number of sites of bronchoalveolar carcinoma. For patients with borderline fitness and smaller tumours (T1a–b, N0, M0), consider lung parenchymal-sparing operations (segmentectomy or wedge resection) if a complete resection can be achieved. Borderline fitness patients have their respiratory function optimised medically and consideration of pre and post-surgical pulmonary rehabilitation, but with consideration of avoiding unnecessary delays to treatment. Offer more extensive surgery (bronchoangioplastic surgery, bi-lobectomy, Pneumonectomy) only when needed to obtain clear margins. Perform hila and mediastinal lymph node sampling or en bloc resection for all patients undergoing surgery with curative intent.

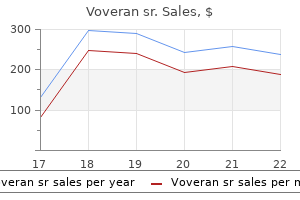

Note that a person who was diagnosed with 2 separate cancers contributed separately to the prevalence of each cancer spasms catheter discount voveran sr 100mg fast delivery. However spasms movie generic voveran sr 100mg, this person would contribute only once towards prevalence of all cancers combined spasms from overdosing discount voveran sr 100mg visa. All cancers combined At the end of 2014 muscle relaxant zanaflex order voveran sr 100mg with mastercard, 431,704 people were alive who had been diagnosed with cancer (excluding basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin) in the previous 5 years. Note that 33-year prevalence has been used because it is the maximum number of years for which prevalence can be calculated using the available data. Prevalence refers to the number of living people previously diagnosed with cancer, not the number of cancer cases. The 5-year prevalence rates were highest for those aged 75–79 and 80–84 and lowest for those under 14 (Figure 7. At the end of 2014, the 65–69 age group was the only group with more than 100,000 people who had been diagnosed with cancer in the previous 10 years. For 10-year prevalence, the 80–84 age group recorded the highest rate of people who had been diagnosed with cancer in the previous 10 years (13% of Australians aged 80–84). At the same time, the 33-year prevalence for all cancers combined was over 110,000 for those aged over 85; this is just under a quarter of all Australians aged over 85 (online Table S7. Percent of population is the percentage of people alive and diagnosed with cancer in the last 5 years as a proportion of the Australian population for the respective age groups. The 5-year prevalence of prostate cancer was higher than for any other cancer At the end of 2014, prostate cancer had the highest 5-year prevalence of all cancers. Among males, prostate cancer had the highest 5-year prevalence (90,354), followed by melanoma of the skin (31,598) and colorectal cancer (29,593). Among females, breast cancer had the highest 5-year prevalence (71,394), followed by colorectal cancer (24,453) and melanoma of the skin (23,530) (Table 7. Life after cancer There are over one million people alive in Australia who have had, or are living with, cancer. The population who have ever been diagnosed with cancer continues to increase due to higher incidence, earlier detection, and advancements in treatment and technology, leading to greater survival. People who have survived cancer often face physical, psychological and fnancial changes as a 7 result of the disease. The management of these changes occurs in addition to the daily requirements those with cancer would have to meet were they not being treated for cancer. Experiences after cancer There is no standard experience ‘It’s interesting that everyone has a diferent story to tell. I’ve spoken with women from regional and outback areas who are isolated from the health-care access we take for granted. I’ve also spoken with women who are still pregnant when they’re faced with a cancer diagnosis. Every person is diferent,’ highlights Suzy, a previous cancer patient now involved with cancer peer support (Cancer Council Australia 2017b). Cancer survivors may be young Younger cancer survivors may experience specifc challenges relating to career goals, intimate relationships, depressive symptoms, managing sexual and fertility anxieties and consequences of premature menopause (Zebrack 2011). Financial changes involve more than numbers As a result of fnancial changes, psychosocial challenges may arise. This may be through stress directly related to money, and/or indirectly by deprivation of the confdence being employed provides and meaningful connections cultivated in workplaces (Wakefeld et al. However, when looking for work post treatment, some seek roles meaningful to their life overall, instead of fnancial reward (McGrath et al. Support these factors—and the associated stressors and reduced quality of life for cancer survivors and their family, friends and caregivers—highlight the importance of follow-up health care and of survivorship as part of the cancer control continuum (National Cancer Institute 2015). In this chapter, the number of cancer deaths relates to deaths where the underlying cause was a primary cancer, and includes basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. In 2019, it is estimated that 49,896 people will die from cancer in Australia, an average of 137 deaths every day. The age-standardised mortality rate for all cancers combined is estimated to be 159 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019. In 2019, it is estimated that the risk of dying from cancer before the age of 75 will be 1 in 10 for males and 1 in 13 for females. By the age of 85, the risk is estimated to increase to 1 in 4 for males and 1 in 6 for females (Table 8. The per cent of all deaths is based on the number of cancer deaths for each sex divided by the total number of deaths for each sex. The per cent of all cancer deaths is the number of cancer deaths for each sex divided by the total number of cancer deaths. More than 4 in 5 deaths from cancer will occur in people over 60 years of age the age-specifc mortality rate of all cancers combined generally increases with increasing age (Figure 8. In 2019, it is estimated that 87% of all cancer deaths in males and 85% of all cancer deaths in females will occur in people aged 60 and over. Fewer deaths from cancer occur in the younger populations: the estimated mortality rate is less than 10 deaths per 100,000 males aged under 35, while females aged under 30 have mortality rates less than 10 deaths per 100,000 females (online Table S8. After 55, the mortality rate rose more steeply for males, to 3,025 deaths per 100,000 for those aged 85 and over. Mortality from prostate cancer contributed to the high cancer mortality rate in older males (Figure 8. Cancer in Australia 2019 93 Cancer mortality rates continue to decline the number of deaths from all cancers combined has risen steadily from 24,915 in 1982 to an estimated 49,896 in 2019 (Figure 8. The number of deaths estimated for 2019 will be the largest number reported in any year to date but some of the increase is due to population growth. In contrast, it is estimated that the age-standardised mortality rate for all cancers combined has decreased by 24%, from 209 per 100,000 in 1982 to 159 per 100,000 in 2019. A decrease in the mortality rate may be due to various factors, such as earlier detection and improvements in treatment. Cancer mortality rate for males continues to fall For males, the mortality rate reached a peak of 287 deaths per 100,000 in 1989 and the rate is 8 estimated to decrease by 32% to 195 per 100,000 in 2019 (Figure 8. The decrease over time can be largely attributed to declines in mortality rates for lung cancer, colorectal cancer and stomach cancer. Actual mortality data from 1982 to 2015 are based on the year of occurrence of the death, and data for 2016 are based on the year of registration of the death (see Appendix C). Colorectal and breast cancers contribute towards decreases in female mortality rates for all cancers combined the cancer mortality rate was consistently lower for females than males. The mortality rate remained fairly steady until 1996, before falling by 20% from 163 deaths per 100,000 females in 1996 to 130 per 100,000 females in 2019 (Figure 8. This decrease can be largely attributed to the decline in the mortality rates of colorectal cancer, breast cancer and cancer of unknown primary site. These 5 cancers are expected to account for around half (48%) of all deaths from cancer in 2019, with lung cancer alone expected to account for nearly 1 in 5 (18%) cancer deaths (Table 3). Lung cancer is estimated to be the leading cause of cancer-related death for both sexes 8 Lung cancer is estimated to be the leading cause of cancer death in both males and females (5,179 deaths and 3,855 deaths, respectively). The estimated risk of death from the disease before the age of 85 is 1 in 20 for males and 1 in 30 for females. The 5 cancers with the highest mortality rates for males are expected to account for around 52% of all estimated cancer deaths in males in 2019; the 5 cancers with the highest mortality rate for females are expected to account for around 56% of estimated cancer deaths in females in 2019 (Table 8. Brain cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death for males aged under 15 Brain cancer causes more deaths in males aged 0 to 14 than any other cancer (Figure 8. Bone cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for males in age groups between 15 and 24. For each of the age groups over 40, common cancers were the leading cause of death from cancer for males (Figure 8. For age group 25–29 years, leukaemia and colorectal cancer were both leading cause of death due to cancer. Leukaemia is estimated to be the leading cause of cancer-related death for females aged 15 to 24 Leukaemia is estimated to account for more deaths in females aged 15 to 24 than any other cancer (Figure 8. The cancers estimated to cause the most deaths for females by age group are similar to those for males, including that brain cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for those aged 0 to 14 and, in older age groups, the leading causes of cancer-related deaths are a selection of common cancers. For age group 0–4 years, leukaemia and brain cancer were both leading cause of death due to cancer.

Buy voveran sr with paypal. आयुरपेन ऑइंटमेंट के फ़ायदे AyurPain Ointment uses side effect composition how to use review.