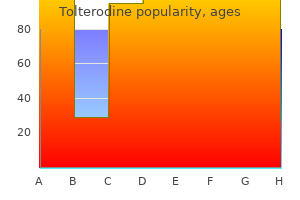

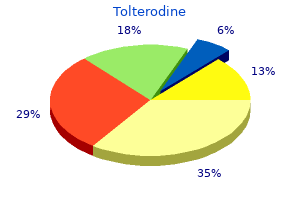

Tolterodine

Menachem Weiner, MD

- Assistant Professor

- Anesthesiology

- Mount Sinai School of Medicine

- New York, New York

The years of labor in animal experimentations symptoms west nile virus cheap 1mg tolterodine overnight delivery, the cost in human effort and in "grants" and the volumes written medicine man gallery tolterodine 1 mg discount, make it difficult to understand how so many investigators could have failed in comprehending the one thing that would have given positive results a decade ago medications you can take when pregnant purchase tolterodine on line amex. This one 62 thing was the size of the dose of vitamin C employed and the frequency of its administration medicine effects buy 2mg tolterodine with mastercard. No one would expect to relieve kidney colic with a five-grain aspirin tablet; by the same logic we cannot hope to destroy the virus organism with doses of vitamin C of 10 to 400 milligrams symptoms 6 days before period due discount 1 mg tolterodine amex. The results which we have reported in virus diseases using vitamin C as the antibiotic may seem fantastic stroke treatment 60 minutes generic tolterodine 4 mg mastercard. These results, however, are no different from the results we see when administering the sulfa, or mold-derived drugs against many other kinds of infections. In the latter instances we expect and usually get forty eight to seventy-two hour cures; it is laying no claim to miracle working, then, when we say that many virus infections can be cleared within a similar time limit [with ascorbic acid] (*These comments are contained in his 1949 paper entitled, "The Treatment of Poliomyelitis and Other Virus Diseases with Vitamin C. The following chapters will briefly summarize the clinical experiences, as reported in the medical literature of the past forty years on ascorbic acid therapy of a wide variety of diseases. Provocative ideas and results will be pointed out and further lines of research with the new genetic concepts in mind, and to start long term investigations of these inadequately explored areas. It will be necessary to break down the sixty-year-old vitamin C mental barriers that have impeded research thus far and to apply some logic to the protocols of clinical research. Ascorbic acid has been thoroughly tried at nutritional levels, over the years, without notable success. Before embarking on the large-scale clinical trials urged in later chapters, further information and additional tests should be conducted to resolve questions in three areas. First of all, the data on the estimated daily production of ascorbic acid in man is based on the results of tests on rats. It would be desirable to obtain additional data on the daily synthesis of ascorbic acid in the larger mammals under varying conditions of stress. In this way we would get a closer estimate of what man would be producing in his liver, if he did not carry the defective gene for L-gulonolactone oxidase. Secondly, even though ascorbic acid is rated as one of the least toxic materials, man has been exposed to such low levels of it for so long that suddenly taking comparatively large amounts, orally, may provoke side reactions in a small percentage of certain hypersensitive individuals. Ascorbic acid in the mammals is 63 normally produced in the liver and then poured directly into the bloodstream. Evidence for these side reactions may be the appearance of gastric distress, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, or skin rashes, all of which disappear on reducing or eliminating the ascorbic acid. Tests should be conducted on these hypersensitive individuals to determine whether their symptoms can be avoided or controlled by substituting the non-acidic sodium ascorbate, by taking the doses with meals, or by gradually building up to the required dosage instead of initially prescribing and starting with the full dosage. Thirdly, research should be instituted to determine the validity of the criticism of stone formation as a consequence of high ascorbic acid intakes. This criticism has been leveled in spite of the fact that these high levels have been normal for the mammals for millions of years and the fact that stone formation has been attributed to a lack of ascorbic acid (see also Chapter 22). It is hoped that the research pathways and protocols outlined the following chapters will serve as a guide for future clinical research to exploit the full therapeutic potential of ascorbic acid for the benefit of man. It is certainly not the intent or the desire of the author that the details of these research proposals be used as the basis for furthering self-medication in any form. We start with the common cold because it is a most annoying ailment and it is one to which everyone is repeatedly exposed. Let us first go over some statistics and current research on the common cold and then take a quick look at the medical literature to see what has been done with ascorbic acid in the treatment of the common cold over the last thirty years. Its cost to industry appears to be well over five billion dollars a year in lost time and production. Much research money is being expended now in the hope of developing a vaccine for colds. The probability of developing a useful vaccine is remote because of the large number of different viruses and associated bacteria found in common cold victims. For instance, the rhinoviruses which can be isolated from more than 65 half the adults with common colds comprise about seventy to eighty different serotypes. Since a vaccine is highly specific and only effective against a particular viral strain or bacterial species, it is doubtful whether a polyvalent vaccine would be useful because of the great number of serotypes and the short duration of induced immunity. What is needed, instead, is a wide-spectrum, nontoxic, virucidal, and bactericidal agent. One of the difficulties in common cold research is the general lack of laboratory animals that are susceptible to this disease. Easily managed laboratory animals such as rats, mice, rabbits, cats and dogs are said not to catch the disease,thus making laboratory studies very difficult. It is significant that the two species that can catch colds, man and the apes, are the two that cannot make their own ascorbic acid. Shortly after the discovery of ascorbic acid, it was found that it had a powerful antiviral activity. This activity was found to be nonspecific and a wide spectrum of viruses were attacked and inactivated. These included the viruses of poliomyelitis, vaccinia, herpes, rabies, foot-and-mouth disease, and tobacco mosaic. The ability of ascorbic acid to inactivate viruses extends to many more and probably covers all the viruses, but these were the ones investigated at this early date. Other workers in the 1930s found that ascorbic acid was capable of inactivating a number of bacterial toxins such as those of diphtheria, tetanus, dysentery, staphylococcus, and anaerobic toxins. The medical literature on ascorbic acid and the common cold from 1939 to 1961 can be divided into two groups: one group contains the clinical tests where the ascorbic acid was administered for the treatment of the common cold at dosage rates measured in milligrams per day (one gram or less); the other group contains those where it was given at higher daily dosages. The milligram group found ascorbic acid to be ineffective in the treatment of colds; the higher-dosage group reported more successful results. Let us skin through this record, covering over a quarter-century, and see what it shows. We will take the inadequate, low-dosage tests first: Berquist(2), in 1940, used 90 milligrams of ascorbic acid per day. Kuttner (3) used 100 milligrams daily on 108 rheumatic children and found no lessening of the incidence of upper respiratory infections. Glazebrook and Thomson (5), in 1942, 200 used between 50 and 300 milligrams daily on boys in a large institution. They reported no difference in the incidence of 66 colds and tonsillitis, and the duration of the colds was the same in the group getting the ascorbic acid and that not getting it. The duration of the tonsillitis was longer, however, in the control group, and cases of rheumatic fever and pneumonia developed; but none occurred in the group getting the ascorbic acid. In 1944 Dahlberg, Engel, and Rydin (6) used 200 milligrams per day on a regiment of Swedish soldiers and reported, "No difference could be found as regards frequency or duration of colds, degrees of fever, etc. At this late date these workers were still proving the pharmacologic fact that you cannot squeeze consistent good therapeutic results from ineffective threshold dosages. Shekhtman (9), in 1961, used 100 milligrams of ascorbic acid for seven months of the year and then 50 milligrams for the rest of the year. These are some of the reports of those who used the threshold of "vitamin-like" dosages of milligrams per day. Now, let us turn to the other side of the picture the group that used higher dosages. This group includes Ruskin (10) who, in 1938, injected 450 milligrams of calcium ascorbate as soon after the onset of cold symptoms as possible. Forty two percent of his patients were completely relieved, usually after the first or second injection. Van Alyea (11), in 1942, found 1 gram a day of ascorbic acid a valuable aid in treating rhinosinusitis. Markwell (12), by 1947, using 3/4 gram or more every three or four hours stated: My experience seems to show that if the dose is given both early enough and in large enough quantity, the chances of stopping a cold are about fifty-fifty, or perhaps better. It is an amazing and comforting experience to realize suddenly in the middle of the afternoon that no cold is present, after having in the morning expected several days of throat torture. I have never seen any ill effects whatsoever from vitamin C and I do not think there are any. The number of patients who have taken large doses of vitamin C to abort colds during in the last three years is considerable large enough to allow an opinion to be formed, at any rate, as a preliminary to more scientific research. Albanese reported his observations in the hope that it would stimulate others to try his treatment and obtain additional clinical data. Woolstone (14), in 1954, obtained good results in treating the common cold with 0,8 grams of ascorbic acid hourly and vitamin B complex three times a day. He stated, "although I can only offer my own observations as proof, the results have been so dramatic that I feel others should be given a chance to try it. In 1958 (15), he published another paper extending his previous good results and recommended 2 to 5 grams of ascorbic acid a day for the prophylaxis of respiratory diseases, nosebleeds, radiation sickness, postoperative bleeding, and other conditions. Bessel-Lorch (16) in tests on Berlin high school students at a ski camp gave 1 gram a day to twenty-six students and none to twenty others. After nine days,nine members of the "no-ascorbic" group had fallen ill and only one member of the "ascorbic" group. All students catching colds were given 2 grams of ascorbic acid daily, which produced a general improvement within twenty-four hours so that increased physical exertion could be tolerated without special difficulties. The significant observation was made that, "all participants sowed considerable increase in physical stamina under the influence of vitamin C medication. One gram of ascorbic acid was given to 139 subjects and 140 others did not receive it. Ritzel stated in his summary, "Statistical evaluation of the results confirmed the efficacy of vitamin C in the prophylaxis and treatment of colds. First, the unheeded appeals for additional extensive clinical research on the high dosage ascorbic acid treatment of the common cold. Second, the levels of ascorbic acid dosages which were considered "high" by these various authors, who still thought of it as vitamin C, were still far below the dosages that would be considered adequate under the teachings of the genetic disease concept. In keeping with this new concept, the following regimen for the control of the common cold has been devised and should be subjected to thorough clinical testing. The rationale is based on the known virucidal action of ascorbic acid and the general mammalian response to biochemical stresses. The strategy is to raise the blood and tissue levels of ascorbic acid, by repeated frequent doses, to a point where the virus can no longer survive. It is really difficult to understand how this simple and logical idea has escaped so many investigators for so long. This regime 68 is not untried: the author has been his own "guinea pig" and has not had a cold for nearly two decades. An individual continuously on the "full correction" regimen of 3 to 5 grams of ascorbic acid daily for an unstressed adult will have a high resistance to infectious respiratory diseases. Should the exposure to the infectious agent be unduly heavy or some other uncorrected biochemical stresses be imposed, the infecting virus may gain a foothold and start developing. Treatment is instituted at the very first indication of the cold starting, because it is much easier to abort an incipient cold than to try to treat an advanced case. If a known heavy exposure to the infectious agent is experienced,such as close contacts with a coughing and sneezing cold sufferer, then prophylactic doses of several grams of ascorbic acid, several times a day, may be taken without waiting for cold symptoms to develop. Within twenty minutes to half an hour another dose is ingested and this is repeated at twenty-minute to half-hour intervals. Usually by the third dose the virus has been effectively inactivated, and usually no further cold symptoms will appear. I watch for any delayed symptoms and, if any become evident, I take further doses. If the start of this regimen is delayed and it is instituted only after the virus has spread throughout the body, the results may not be so dramatic, but ascorbic acid will nevertheless be of great benefit. Continued dosages at one or two-hour intervals will shorten the duration of the attack, often to a day. The great advantage of this common cold therapy is that it utilizes a normal body constituent rather than some foreign toxic material. This regime should be the subject of large scale, long-range clinical studies in order to establish its efficacy and safety, and to provide the data required by medicine for any new suggested therapy. As a result of his successful personal experience and other work, he published in 1970 the book (18) Vitamin C and the Common Cold. This volume, the first published book in the new fields of megascorbic prophylaxis and megascorbic therapy, gives a more detailed and practical account of the use of ascorbic acid for this condition than is possible in the space of this short chapter. With the publication of this book, there was a rash of unjustified criticism heaped upon Dr. Up to the date of the publication of this book, the author is not aware of any clinical tests planned or started that follow the suggested regimen of: 1. Three groups are generally recognized: the viral diseases, the bacterial infections, and the diseases caused by more advanced types of parasitic agents. It so happens that this classification also denotes the relative size and complexity of the infectious agents. The viruses are the simplest and most primitive forms; in fact,they are sort of transitional substances between living and nonliving matter. They cause a wide variety of diseases such as poliomyelitis, measles, smallpox, chicken pox, influenza, "shingles," mumps, and rabies. The common cold, discussed in the previous chapter, is a virus disease, although various bacteria generally infect the weakened tissues as secondary invaders. When a virus infects a mammal and gains a foothold in the mammalian body, the mammal reacts by showing the symptoms of the disease and at the same time organizes its own biochemical defenses against the virus. In nearly all mammals,this biochemical defensive reaction is at least twofold: the victim starts to product antibodies against the virus and also increases the rate of ascorbic acid synthesis in its liver. This is the normal mammalian reaction to the disease process, except in those species, like man, that cannot manufacture their own ascorbic acid. Let us see what a review of the medical literature reveals about megascorbic therapy and viral disease: 71 Poliomyelitis the application of ascorbic acid in the treatment of poliomyelitis is an incredible story of high hopes that end in disappointment, of blunders and lack of insight,of misguided labors and erroneous hypothesis. And then, when a worker finally seemed to be on the right path and had demonstrated success, hardly anyone believed his results, which were systematically ignored. Within two years after the discovery of ascorbic acid, Jungeblut (1) showed that ascorbic acid would inactivate the virus of poliomyelitis.

If the direction of the resultant accelera tion in Figure 3-5 (Axz for the pilot and Ayz for the flight engineer) is accepted as upright treatment 02 academy cheap tolterodine 2mg without prescription, the pilot will perceive a backward tilt and the flight engineer will perceive a leftward tilt symptoms magnesium deficiency order tolterodine 1 mg without prescription. However medications peripheral neuropathy order tolterodine cheap, both would be likely to perceive a nose-up attitude of the aircraft symptoms for pregnancy order tolterodine in united states online, assuming that each is aware of his orientation relative to the aircraft medications prescribed for pain are termed purchase discount tolterodine. In Figure 3-4 medicine used during the civil war cheap 2mg tolterodine overnight delivery, the vector (G) representing gravity is a downward-directed arrow, whereas in Figure 3-5 it is an upward-directed arrow (g). This incon sistency was purposely introduced to illustrate that there is some variation in aerospace medicine in regard to the directional representation of force vectors. There is a choice as to which of the following shall be represented (1) the action of a force on the body, or (2) the reaction of the body to the force. When an aircraft in level flight increases forward speed, vectorial representation of the ac celeration and of the force applied to the pilot by the back of the seat would be forward, as il lustrated in Figure 3-6A. The body reacts to this force by an equal and opposite backward directed (inertial) force (Figure 3-6B), and since the body is not rigid and is not of uniform densi ty, some organs within the body will be displaced slightly backward relative to the skeletal system. Likewise, the seat is applying an upward-directed force, equal and opposite to the weight of the man on it. However, the effect of gravitational attraction is to displace organs downward relative to the skeletal system, just as though the man were being accelerated upward. If actions of the seat on the man are represented, that is, if the forward acceleration is represented by a vector pointing forward, then gravity must be represented by an upward-directed vector as in Figure 3-6A. If reactions are represented, that is, direction of displacement of body organs relative to skeletal system, then the x-axis vector must point backward and the gravity vector downward as in Figure 3-6B. Note that the length and line-of-action of resultant vectors (heavy black arrows) are the same in Figures 3-6A and B, whereas the resultant line-of-action represented in Figure 3-6C is incorrect because a mixture of action and reaction vectors has been used. Different perceptions of tilt in a pilot and flight engineer in an aircraft accelerating during level flight. The resultant of the linear acceleration and gravity rotates toward the x axis in the pilot and toward the y-axis in the flight engineer. For man-referenced reaction vectors, +Gz is usually defined as the head-to-seat direction (see Chapter 2), whereas for action vectors as defined by Figure 3-2, +Az is defined as the seat-to-head direction. In the aerospace environment, unusual linear and angular accelerations occur frequently. The occurrence of a single, exceptional linear or angular acceleration component can induce disorien tation or vertigo, but more typically, one must consider combinations of stimuli to appreciate troublesome situations. To comprehend the functional significance of unusual stimuli combina tions, it is helpful first to appreciate the coding of normal vestibular messages that occur in natural movement. In natural movement, whenever the head is tilted away from upright posture, the semicircular canals and otoliths always provide concomitant, synergistic messages. During the head tilt, the utricular otoliths would slide backward, trigger ing change-in-position receptors as well as position receptors in a pattern signifying a position change about the y-axis, and the final coded utricular position information would be predictable from the preceding change-in-position information. Likewise, it has been shown that integration of the angular velocity information from the semicircular canals can be subjectively performed to obtain an angular displacement estimate equal to the position change which has occurred (Guedry, 1974,50-56), and hence, equal to that signaled by the otoliths. When the head is turned about an axis that is aligned with gravity (for example, the head turns about the z-axis in upright posture or about the y-axis while lying on one side), the semicircular canals are stimulated, but there is no change in orientation of the otolith system relative to gravity, and hence, no change-in position information from the otolith system. Under this circumstance, that is, when the axis of rotation signaled by the semicircular canals is aligned with the gravity vector as located by the otolith system, these two classes of vestibular receptors do not reinforce one another, but it should be noted that there is no conflict in their information content. During forward acceleration of the aircraft, the resultant linear acceleration, Ax2, rotates from alignment with the pilots z-axis forward toward his x-axis through an angle designated as As was pointed out earlier, this is the same change relative to the existing force field that would occur if head and body were simply tilted backward relative to gravity 15 degrees. However, during the tilting process, the vestibular message would be quite different in these two situations. In the latter situation (real tilt), the synergistic messages from the semicircular canals and the otolithic receptors as described above would be present. During the dynamic phase of the stimulus in the former situation (forward acceleration), change-in-position and position information from the otolithic receptors would be unaccompanied by synergistic in formation from the semicircular canals. However, if the forward linear acceleration is sustained for a while, then, in this steady state condition, the otolithic position input would signal tilt, and, as in static tilt relative to gravity, otolithic or semicircular canal change-in-position information would be absent. In this case the individual would experience backward tilt as though he were tilted relative to gravity, but only after a delay or lag. Each of the conditions just described, except sustained horizontal linear ac celeration, occurs in natural movement, and each produces a pattern of vestibular input that is familiar and perceived quickly and accurately if the observer chooses to attend to it. In subse quent sections of this chapter, conditions of motion will be described that produce conflicting vestibular inputs, and these are usually confusing, disturbing, disorienting, and nauseogenic. In partial summary, the semicircular canals localize the angular acceleration vector relative to the head during head movement and contribute the sensory input for (1) appropriate reflex action relative to an anatomical axis and (2) for perception of angular velocity about this axis. Percep tion of how this axis is oriented relative to the Earth depends upon sensory inputs from the otolith and somatosensory systems, and thus, appropriate reflex actions relative to the Earth depend upon these other systems working synergistically with the semicircular canals. The otoliths pro vide both static and dynamic orientation information (relative to gravity) and contribute to the perception of tilt and also to the perception of linear velocity. The perception of linear velocity derives from a combination of (1) change-in-position information from the otoliths and (2) the absence of angular velocity information from the canals. The otoliths provide change-in-position information when the cilia are in motion, and the stimulus required is change in linear accelera tion. Spatial Disorientation in an aviator, spatial disorientation usually refers to the inaccurate perception of the attitude or motion of his aircraft relative to the coordinate system constituted by the Earths surface and gravitational vertical, and it can endanger flight safety. Spatial disorientation has been estimated to account for between four and ten percent of major military aircraft accidents and even higher percentages of fatal accidents (Gillingham & Krutz, 1974, p. From 1977-1981, disorientation was a direct or contributing cause of 31 percent of pilot-error accidents in the U. Disorientation is a normal reaction in many conditions of flight, and it is probably experienced by all pilots at one time or another. It illustrates that there are similarities in disorientation encountered in different types of air craft and also across a span of 14 years (Clark, 1971). The implications of disorientation incidents range from fatal accidents to inconsequential events that may be instructive to the pilot. Between these extremes are nonfatal accidents, aborted missions, mission degradation, and mission completion but with persisting unfavorable effects on the pilot. A number of factors combine to determine the consequences of a disorientation inci dent. Sufficient altitude with no other plane or object nearby can provide abundant recovery time and reduce risk, and conversely, prox imity to the Earths surface or other aircraft increases risk. This factor and its relation to items in Tables 3-1 and 3-2 are obvious and will not be elaborated here, but it is a factor that predominates and influences all others. When the ac tion is taken, the response of the aircraft may prompt an instrument check which ordinarily will lead to proper corrective action. An important exception occurs when the conflict between an im mediate false perception of aircraft orientation and instrument information provokes an ex cessive emotional reaction; then the pilot remains at risk. Most importantly, the pilot may remain unaware of his disorientation until it is too late for corrective action. In formation flight the pilots attention is focused on another aircraft, and the perceived aircraft altitude often differs drastically from true altitude because the pilot has been concentrating on maintaining position relative to the other aircraft. Severe disorientation revealed by shift of attention to flight in struments delays appropriate corrective action beyond the point of no return due to proximity of other aircraft or the ground. Naval Flight Surgeons Manual On the other hand, there are many maneuvers which induce disorientation, but the pilot is so aware of its occurrence that he may not be at all disturbed by it. For example, a plane flying in a level, coordinated, gentle bank and turn may be perceived as though it were in straight and level flight for reasons made clear in earlier sections and illustrated in Figure 3-7. The pilot who in itiates the maneuver knows what to expect, and for this reason, the perceptual experience seems natural and is consistent with the intellectual information derived from his instruments. A pilot may not even refer to a false perception of the planes attitude as disorientation if he is keep ing track of the flight situation. This was illustrated by comments from an experienced F-4 pilot who, while serving as a backseat subject in an in-flight experiment, reported that a head move ment induced an apparent 30 to 40 degree nose-down attitude of the aircraft which at the time was in a 2 g level bank and turn. When this experience was later referred to as an example of disorien tation, the pilot-subject denied that he was disoriented at all because he was completely aware of the true attitude and condition of the aircraft. The dangerous aspects of disorientation are considerably diminished if the pilot alertly keeps track of the true condition of the aircraft. When disorientation inputs become second nature to him, perceptual motor reactions are probably modified and, in their modified form, may even enhance his control of the aircraft. In a coordinated turn, the aviator may ac cept the resultant vector as gravitational vertical. Here, the magnitude (or persistence) of the erroneous perception is a threat to the pilot. As in the case of the unanticipated disorientation, control of the aircraft may be jeopardized through the deleterious effects of hyperarousal (cf. Several points emerge from these considerations of the etiology of dangerous disorientation conditions: (1) Familiarity with conditions that produce disorientation and a second-nature anticipation of its occurrence can reduce its serious im plications and may even be useful to the aviator; (2) Failure to keep track. For these reasons, training concerning conditions that can be ex pected to produce disorientation will have beneficial effects, and occasional refresher training is a worthwhile measure for the experienced aviator, especially after a period away from flying. Visual-Vestibular Interactions Relevant to Aviator Vision Tbe Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex the vestibulo-ocular reflex influences vision during natural movement much more than is generally appreciated, and it is capable of subtle and occasional profound influence on vision in aviation. Most physicians or physiologists think of nystagmus, an oculomotor pattern which oc curs in certain unnatural motion profiles and in pathologic states, in relation to vestibular stimulation, but nystagmus is probably the least typical form of the vestibulo-ocular reflex in healthy individuals during natural movement. A more common oculomotor response consists of nearly smooth, sinusoidal eye oscillations that almost perfectly compensate for head oscillations that occur during walking, running, or simply shaking ones head, as in signifying yes or no. For example, in the latter situation as the head turns right, the eye turns left, thereby com pensating for the head movement (cf. Gresty and Benson (in preparation) describe fairly high-frequency components (in the range 1 to 10 Hz) in angular oscillations of the head dur ing whole-body movement and also in aircraft. It is important to note that the visual system is very poor at tracking Earth-fixed targets at these frequencies if it is unaided by the vestibulo ocular reflex. Therefore, this reflex plays an important role in stabilizing vision relative to the Earth during many kinds of natural motion. The reader can demonstrate this to himself by holding his head stationary and oscillating this page back and forth on a desk top at a frequency just sufficient to blur the print. To complete the demonstration, and this is the crux of it, oscillate your head at the same frequency while the page remains stationary on the desk top, and observe that the print remains perfectly clear. The vestibulo-ocular reflex automatically stabilizes the eyes relative to external 3-21 U. Naval Flight Surgeons Manual visual surroundings during head movements to maintain visual acuity for Earth-fixed targets. This is the reason that individuals without vestibular function report jumbled vision during motion, especially vehicular motion involving vibratory oscillation. However, following loss of vestibular function, the influence of neck proprioception on eye movement may increase to im prove ocular stabilization during voluntary movement. This highly advantageous vestibular-ocular reflex can become disadvantageous (inappropriate), however, in aircraft, surface ships, or other moving platforms since the head moves in inertial space, while visual displays, such as aircraft instrument panels, may move in unison with the head. If there is a tight coupling between head and display during such move ment, then at certain frequencies and peak angular velocities, the vestibulo-ocular reflex will in terfere with vision for the display (Guedry & Correia, 1978). Vision and the Dynamic Response of the Cupula-Endolymph System the probability of encountering problems with vision and also with disorientation in a given flight environment depends, among other things, on the dynamic response of the cupula endolymph system to various profiles and frequencies of angular acceleration. Understanding this aspect of vestibular function is therefore helpful in analyzing problems arising from pathological conditions during natural movement or from normal responses to unusual motion. Because the cupula-endolymph ring has the structural characteristics of an overcritically damped torsion pendulum, its behavior and that of the responses it controls are theoretically predictable when acceleratory movements of the head are known. Much information was accumulated to in dicate when such predictions are accurate and when they are not (cf. Figure 3-8 il lustrates predicted changes in cupula displacement relative to the skull throughout two motion conditions. Figure 3-8A, depicting cupula deflection during a simple, natural head turn to the left, illustrates several important points. Notice that the cupula deflection curve looks like the stimulus angular velocity curve and are not like the angular acceleration curve. In natural head turns, the dynamic response of the end organ is such that the input sensory message matches the instantaneous angular velocity of the head relative to the Earth (like a tachometer), even though angular acceleration is the effective stimulus. For this reason, the turning sensation (subjective angular velocity) controlled by cupula deflection is accurate during and after the turn. Similarly, the vestibulo-ocular reflex is accurate during natural turns in that the reflexive eye velocity com pensates for the head velocity and stabilizes vision relative to Earth-fixed targets. In contrast, Figure 3-8B illustrates vestibular effects of an unnatural motion involving sustain ed rotation. Inertial torque deflects the cupula during the initial brief angular acceleration, but it is absent during the following constant angular velocity. Consequently, the cupula, because of its 3-22 Vestibular Function restorative elasticity, returns toward rest position. Then, being near rest position when decelera tion occurs, it is deflected in the opposite direction by the inertial torque from the deceleration (angular acceleration in the opposite direction). The turning sensation controlled by cupula deflection is accurate only during the initial acceleration. During constant velocity, the sensation of turn will diminish and stop; then, the deceleration will produce a reversed sensation of turning which can persist for 30 to 40 seconds after stopping. Obviously, with the unnatural stimulus, the semicircular canals do not perform their velocity-indicating function satisfactorily, and their in put can be the basis of disorientation and impaired visual performance. Comparison of cupula deflection during a natural short turn (A) and during a sustain ed turn of several revolutions (B). Naval Flight Surgeons Manual this unnatural stimulus produces the particular pattern of oculomotor response called nystagmus. During the initial acceleration in Figure 3-8B, the eyes drift right (relative to the skull) as the head turns left. This drift, which compensates approximately for the turn, is called the slow phase of nystagmus, but as the head continues to turn, the eyes recenter themselves, that is, catch up, by a fast or saccadic eye movement called the fast phase, which has extremely high velocity (300 to 600 degree/second). Because the directions of the slow and fast phase of nystagmus are opposite, there has been inconsistency in designation of the direction of nystagmus. When viewed by a medical examiner, the fast phase (saccade) is easiest to see, and this led to the convention of designating nystagmus direction by its fast phase relative to the ex aminee.

In most of these cases medicine man pharmacy buy genuine tolterodine online, the role of vibration has not been firmly established medications i can take while pregnant purchase tolterodine 2 mg without prescription, and much work remains to be done in the area medicine 4h2 cheap 4mg tolterodine overnight delivery. A number of countries symptoms 13dpo tolterodine 1mg without prescription, including the United States symptoms just before giving birth order tolterodine 2 mg with visa, are currently in the process of adopting these or similar standards symptoms you have cancer discount 2mg tolterodine with amex. Protection Against Vibration Protective measures against vibration fall into three general categories: control at the source, control of transmission, and attempts to minimize human effects. Control at the source is primarily a problem of engineering, and it will not be discussed further in this chapter. The use of high-damping materials in new con struction and damping treatments of existing equipment can reduce structural resonance, which in turn, reduces transmission. Isolating the individual from the vehicle by means of resilient seat cushions and the like is another method of reducing transmission. The usefulness of this tech 2-30 Acceleration and Vibration nique is necessarily limited when dealing with ejection seats. The dynamic overshoot of a cushion during ejection could cause an unacceptable increase in the +Gz impact acceleration ex perienced by the aviator. The adverse effects of vibration that reach the body can, in some cases, be substantially re duced. For example, one study of vibration transmission through the trunk to the head showed variations as great as six to one, contingent only on changes in posture (Griffin, 1975). Proper design of displays and flight controls can lead to a cockpit en vironment that is both more tolerable and more functional during vibration stress. With physical fitness, training, and experience, a considerable amount of adaptation may take place in the aviator. In addition, motion sickness induced by vibration often responds to the standard phar macological remedies. Advisory publication 61/103F, methods for assessing visual end points for acceleration tolerance, 1986. Combining techniques to enhance protection against high sustained accelerative forces. Vertical Vibration of Seated Subjects: Effects of Posture, Vibration Level, and Frequency. Performance and physiological effects of acceleration induced (+Gz) loss of consciousness. An in-depth look at the incidence of in-flight loss of con sciousness within the U. Spinal injury after ejection in jet pilots: Mechanisms, diagnosis, followup, and prevention. Naval Flight Surgeons Manual Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 1975, 46, 842-848. The forward facing position and the develop ment of a crash harness (Air Force Technical Report 5915). Disorientation (vertigo, dizziness, tumbling sensations), nausea, and vomiting, episodes of blurred and unstable vision, and impaired motor control (disequilibrium) are effects which can occur singly and in various combinations as a result of either exceptional environmental stimuli or episodic vestibular disorders or both. In the aviation environment, the symptoms may be normal reactions to misleading or inadequate sensory stimuli, but they may be coupled with requirements for controlling a high performance aircraft in three-dimensional space. In pathological states, the symptoms result from disordered transduction of central processing of head accelerations, and this is likely to be coupled with requirements for control of head and body motion. In either case, the origin of the aberrant reactions lies in inadequate or misleading information about the state of motion or orientation of the body relative to Earth, and ultimately this constitutes a threat to sur vival. It is natural, then, that unexpected occurrences of such reactions can be very disturbing. The parallel between pathological states and exceptional environmental conditions can be taken farther. When unnatural motion conditions are frequently experienced, a state of adaptation is frequently achieved in which the disturbance and disequilibrium initially elicited, gradually abate; perceptional aberrations disappear, and control of motion approaches a desirable state of automaticity. Naval Flight Surgeons Manual pace with a very gradual loss of function, such that no symptoms are experienced. Attention to this parallel is of probable practical importance to both the civilian practitioner and the specialist in aviation medicine. An understanding of the perceptual aberrations and reflexive actions generated by unusual motion stimuli and the process of adaptation to those stimuli may increase our understanding of the symptomatology generated by various disease states, and of course, the converse is also true. Structure and Function of the Vestibular System the vestibular system, almost like sensors in an inertial guidance system, detects static tilt of the head relative to the Earth, change in orientation of the head relative to the Earth, and linear and angular accelerations of the head relative to the Earth. These sensory messages are set off ear ly in life by passive, involuntary movement, and they probably play an important role in develop ment (Guedry & Correia, 1978; Ornitz, 1970). Not long thereafter, however, vestibular messages are frequently elicited by active, voluntary movement, and then they play a role in development of skill in the control of whole-body movement. In ambulatory man, the head is the uppermost motion platform of the body, and to be functional, vestibular messages must be integrated with proprioceptive and visual inputs. Vestibular messages coordinate with these other sensory systems in setting off reactions that reflexively adjust the head, eyes, and body for automatic control of motion. In this chapter, it is assumed that the reader is familiar with the basic anatomy and structure of the vestibular system. However, as a reminder, some basic information about this system will be presented along with a nomenclature convenient for describing stimuli to the vestibular structure. Figure 3-1 illustrates anatomical features of the semicircular canals and of the utricle and saccule. The major planes of the semicircular canal ducts relative to the cardinal head axes are shown in the insets. A gelatinous cupula protrudes into the ampulla of each semicircular duct and serves as a sensory detector of angular accelerations in its plane. Gelatinous pads, one in the utricle and one in the saccule, have calcite crystals imbedded in their surfaces and are sensory detectors of linear accelerations of the head. With saccular destruction, the small duct to the utricle may close, possibly preserving the functional integrity of the utricle and semicircular canals. This possibility is speculative, but it may account for early experimental results indicating lesser equilibration disturbance after sac cular as compared with utricular ablation. Utricular ablation would destroy the integrity of both the semicircular canals and utricle. If there is an angle between the plane of the canal and the plane of the angular acceleration of the head, then the effective stimulus to the canal, is given by. Angular acceleration is independent of the distance from the center of rotation, and the semicircular canals are not responsive to linear accelerations, probably due to the close similarity in specific gravity of the cupula and the endolymph. Recently it has been suggested that substan tial contact between the cupula and the interior membranous ampullary wall, all around the periphery of the cupula, would limit deflection of the cupula to its central portion, like the move ment of a drum. If correct, this could further reduce responsiveness to this system to linear ac celeration. Therefore, a person seated with head erect at the center of rotation of a vehicle undergoing angular acceleration would receive the same stimulus to the semicircular canals as another person seated with head erect five meters, or farther from the center of rotation. The lat ter would, of course, be exposed to much greater centripetal and tangential linear acceleration, and hence a different otolith stimulus than the former, but the stimulus to the semicircular canals would be theoretically identical. Analysis of the inertial forces and torques which displace the utricular and ampullar sense organs involves a branch of physics referred to as kinetics, but these forces and torques are pro portional to linear and angular accelerations of the head. Therefore, the commonly used kinematic descriptions of linear and angular accelerations of the head are sufficient for specifying vestibular stimuli. When linear acceleration is represented as a vector, the arrowhead points in the direction of acceleration and its length represents its magnitude, but in order to be physiologically mean ingful, it must be man-referenced. Gross morphology of the membranous labyrinth and cochlea (adapted from Correia & Guedry, 1978). Linear and angular ac celerations are vectors that must be specified in relation to anatomical coordinates of the head in order to be properly described as vestibular stimuli. These head axes, as defined by Hixson, Niven, and Correia (1966), provide a clear anatomical reference to which stimulus parameters can be related. Relations between this and the nomenclature used in Chapter 2 are clarified in Figure 3-6. Linear and angular accelerations are vectors that must be specified in relation to anatomical coordinates of the head in order to be properly described as vestibular stimuli. These head axes, as defined in Hixson, Niven and Cor reia (1966), provide a clear anatomical reference to which stimulus parameters can be related. Angular acceleration is the rate of change of angular velocity and it can be expressed in 2 2 any angular unit like deg. Angular acceleration can also be represented as a vector, as illustrated in Figure 3-2. The angular acceleration vector must be drawn in alignment with (or parallel to) the axis of rotation, and its arrowhead end is determined by following the right-hand rule: When angular velocity is increas 3-5 U. Naval Flight Surgeons Manual ing, point the curled fingers of the right hand in the direction of rotation, and when angular velocity is decreasing, point the curled fingers opposite the direction of rotation; in each case, the thumb determines the direction of the arrowhead. Since the vector is perpendicular to the plane of rotation, a simple way to envision its effectiveness in stimulating a semicircular canal is to im agine that the canal has an axis. If the vector and canal axis are aligned, then would be maximal ly effective in stimulating the canal. The angle between the canal axis and the angular acceleration vector is the same as the angle mentioned in a preceding paragraph. Thus, (Figure 3-2) would stimulate the lateral (or horizontal) canals and not the vertical canals. Sensory Transduction of Head Motion into Coded Neural Messages There is a spontaneous activity in the vestibular nerve. If the head starts to turn left about the z-axis the rings of endolymph in the two lateral (horizontal) canals tend to lag behind due to inertia, thereby deflecting the cupula, as illustrated in Figure 3-3. In the lateral canals, deflec tion of the cupula toward the utricle (utriculopetal deflection) increases the rate of firing of the left ampullary nerve, while deflection away from the utricle (utriculofugal deflection) in the right lateral canal decreases the firing rate. In the vertical canals (the anterior and posterior canals), utriculofugal cupula deflection increases firing rate, while utriculopetal deflection decreases it. Note that the ability of each canal to increase or decrease the rate of discharge of its ampullary nerve has important functional significance. It means that a single canal is capable of signaling rotation in either direction in its plane. Also a single intact inner ear, due to the orthogonal ar rangement of the three semicircular canals in each ear, is capable of signaling direction of rotation in any plane of head rotation. Figure 3-3 is also convenient for visualizing expected initial reac tions to peripheral vestibular disorders. The otolithic sensory organs in the utricle and saccule respond to linear acceleration and to tilts of the head relative to gravity (Figure 3-4). Calcite crystals at the surface of the gelatinous plaques that comprise the utricular and saccular sense organs have a specific gravity of 2. The surface of the utricular otolith membrane is slightly curved, but its plane is approximately parallel to that of the lateral semicircular canals. Linear ac celeration, acting parallel to the place of the otolith membrane (frequently referred to as the 3-6 Vestibular Function shear direction), is considered the effective stimulus to this sensory system (Fernandez, 2 Goldberg & Abend, 1972). As in the ampullary nerves, there is spon taneous firing of the utricular and saccular nerves. The hair cells at the base of the utricle are shown diagrammatically in Figure 3-4. Hairs projec ting upward from each cell have a morphological polarization determined by the position of one lone distinctive kinocilium relative to rows of stereocilia diminishing in length row by row with distance from the kinocilium (Lindeman, 1969). It has been found that deflection of the hair bundles toward the kinocilium increases the neural discharge rate, whereas opposite deflection decreases the discharge rate relative to the spontaneous level. All cells point toward a hook shaped striola that curves through the macular utriculi, and a similar arrangement exists in the saccule. It is also the morphological polarization of hair cells in the cristae of the semicircular canals that determines which direction of cupula deflection increases the neural firing rate. Therefore, direction of tilt of the head is signaled by different topographical patterns of discharge in the utricular nerve. For example, if the head were tilted forward, the cells depicted in Figure 3-4 would be relatively unaffected, that is, the spontaneous firing rate would be approximately main tained, but neural activity triggered by other cells in other locations within the macula would be changed significantly. Amount of tilt in a given direction would be signaled by the amount of change of a specific unique pattern for that direction of tilt relative to the spontaneous firing level. The otolithic receptors have both static and dynamic functions (Fernandez & Goldberg, 1976; Goldberg & Fernandez, 1975) that is, in addition to signaling static position of the head relative to gravity, some nerve fibers from the utricle and saccule respond to change in position. These latter units respond when the otolith membrane is moving relative to the underlying hair cells, thus they respond to change in linear acceleration. This ability of the otolithic receptors to supply both position and change-in-position information will be discussed below in terms of their potential contributions to spatial orientation. Neurophysiological studies also indicate that with sustained tilt, there is some evidence of adaptation in some position-sensitive units. Direction of endolymph displacement (arrows in the lateral semicircular canals) dur ing angular acceleration of the head to the left (counterclockwise as viewed from above). Dashed lines indicate cupula displacement which deflects hairs projecting into cupula. The inset hair cell illustrates stereocilia relative to the kinocihum (dark hair). Deflection of the hair bundle toward the kinocilium increases neural discharge, while deflection away from the kinocilium decreases neural discharge relative to spontaneous level.

For some un known reason living on oatmeal seems to promote dental caries and rickets treatment under eye bags order line tolterodine. The worst teeth in the world may be seen in Scotland medicine 223 buy discount tolterodine 2mg, where oatmeal is given high rank as a food symptoms 7 days after conception cheap tolterodine 4mg fast delivery. Then enough saffron and sliced stuffed olives and cooked mushrooms and parsley symptoms of colon cancer buy tolterodine 4 mg with mastercard, or perhaps shaved and fried sweet peppers medicine vocabulary tolterodine 2 mg on-line, are added to make an attractive dish medicine keeper cheap tolterodine 1mg mastercard, which is then fried in butter, drip ping, olive oil, or corn oil. Children can be trained to like that every day, but it is not a substitute for fat meat. Corn, in the form of hominy grits, or the big hominy called samp, or corn meal, can be substituted for potatoes or rice. The northern Italians often serve the corn meal mush they call polenta twice a day. Of the spices, real ground black pepper and freshly ground paprika and saffron are outstanding. Some people even have the evil habit of adding salt to food before they taste it, which is, of course, an insult to the cook. Young carrots cut in strips and cooked with a little syrup are a lot more appetizing than the soggy cross sections usually served. Everyone, I suppose, has some pet dislikes, and one of mine is the combination of peas and carrots served in cheap restaurants. Golden Cross bantam corn right out of the garden and served with plenty of butter is one of the taste treats in this world, and it is generally well tolerated. When the ears are a little past their prime, a thin knife blade can be run down each row and the milk of the corn squeezed out with a tablespoon. Extracting the milk from the corn is a messy job, but a good cook can do wonders with it. The canned yellow creamed corn is a good thing to have in the house, even if it contains a lot of husks and is diluted in various ways. That old country dish of mashed turnip and potato, and butternut squash, and pump kin for pie filling are all good. The indigestible cellu lose covering causes a lot of flatulence and general intestinal unhappiness. But beans have a high protein content and if some smart canner could just figure out a mechanical rather than a chemical method of getting the hide off them they should be a fine food. After there weThe enough of them, and it took plenty, they were baked with a big square of home-cured salt pork. The trick in that seems to be to use six parts of real olive oil to one part of wine or tarragon vinegar and any other flavoring that is liked. Fresh celery with the strings removed and cut crosswise in quarter inch slices and then served with a fine dressing is first rate. Raw oranges, apples, strawberries, tomatoes, and peaches can trouble lots of folks. In season blueberries, raspberries, dead-ripe pineapple and melons, and plums can be agreeable. In a well-run home delicate fruits like raspberries and seedless grapes and blue berries can be spread out and every rotten one picked out. After that they can be placed in the dish they are to be served in and put in the icebox to chill. Bananas which have never been frozen should be kept at room temperature until freckled. One embittered soul figured out that only one in six hun dred of the honeydew melons and canteloupe that flood into New York City in season will ever be fit to eat. The middle of the side, not the end, should press in and stay in like a ripe apple and a fine perfume should be noticeable. They usually have a poor taste unless oil from the skin is added, and that can be quite irritating. You could journey from New York to Florida, stopping at restaurants along the way, and never find grapefruit properly prepared. The membrane between the cells is indigestible, so each partition should be cut around inside with a thin sharp knife and the seeds, if any, removed. When you get through eating such a grapefruit portion a perfect framework remains. Grapefruit and grapes are a great cross to the managers of private and public restau rants, since there seems to be no way of serving them any way but ripe. But pears and bananas and melons and alligator pears and pineapple can all be served as green as grass, then nothing is lost by getting overripe. Such fruits are almost as bad as the sliced green tomatoes faintly tinged with pink that are served with steak. Reinforcing them with the juice of one half of a fresh grapefruit, or a cut-up freckled banana, or peeled and seeded grapes, can add to the enjoyment of eating them. The natives may have been immunized over the centuries to the local infections, but when strangers go there they are fair game. Even cleaning teeth with tap water and toothpaste can start the forty bowel movements a day. A good rule in the tropics is never to drink plain unboiled water, even if especially bottled. One quarter of a glass of wine and three quar ters of a glass of water usually is a safe drink if allowed to stand a few minutes. In some of the tropical countries local superstition has it that washing dishes in hot water causes rheumatism in the hands, so dishes are washed in cold water. Strong sugar solutions used to pre serve fruit seem to discourage virulent bacteria. The housewife should use sugar for the preparation of fruit compote or canned fruit, and if any of her children are under weight it can be added to raw fruit and rice. It is a very concen trated carbohydrate and in the form of commercial candy can apparently increase cavities in soft teeth at a tremendous rate. Many children need to eat five or six times a day and natural sugars like ripe bananas and dates and figs and seedless raisins are excellent tidbits to have on hand. Maple syrup is a good thing to serve with corn cakes and yeast-risen buckwheat cakes. Desserts other than canned and raw fruit pose a problem for many allergic families. The children may get some pleasure and value out of puddings and pie fillings, but cake and cookies should be kept out of the picture, which is too bad. When a woman is full of pent-up nervous energy nothing seems to relieve her quite so much as making a batch of what are called "brownies," and they can raise the very devil if any of her children have skin trouble or soft teeth. Rice pudding with raisins and tapioca pudding require baking longer than that and are good healthy desserts. A passable pie crust which will not roll but can be patched together can be made by an artistic cook out of potato flour and ice water and sugar and butter. It might be a good thing for the country if the top crusts on pies were all eliminated. If people could get the idea that the top crust is fattening it would be an advance. Not that top or bottom makes any difference, of course, but it is easier to abandon the bottom crust. Butternut squash, pumpkin, mince, ap ple, plum, and peach pie filling can be wonderful culinary adventures. But, owing to the commercial bakeries, good pie made without chemicals is fast disappearing from the Ameri can cuisine, and that is too bad. An easy fortune awaits any one who can restore good pie with no top crust to New York City. The temperature of the water should be just below boiling, otherwise an irritating substance called mercaptan will be extracted. In parts of the country there are so many de grees of hardness in the water that it is impossible to make good tea or coffee, in which case distilled water should be used. Many people over the age of sixty-five should not ex pect to fall asleep readily for hours after drinking a cup of tea or coffee, so they may have to dispense with it for the evening meal. There seems to be little advantage to extract ing part of the caffeine in special preparations of coffee. I just want to em phasize that the housewife, with her power of the purse and her way of preparing her purchases, controls our destiny. It seems probable that the eternal economic plight of our farmers has a simple explanation. Little of the grain and milk and chicken and eggs and vegetables raised today can be classed as needed. Two acres of grassland on a hilly New England farm will furnish the same energy for a steer as one hundred and sixty acres of pasture land in certain areas of the West. Private capital could take over a whole county in New Eng land for use as a pilot plant. With a processing plant and a collecting system, every farmer in the county could be put to work raising animals. With most of them going forward to animal husbandry, we could relegate plows to the Smithsonian. And a muddy stream means that we are dissipating our great est natural resourcea our topsoil. Postscript Reading over this manuscript has made me realize that my dear wife is right, as usual. When the writing has been a bit on the dull side it is because I have been too weary. They are wonderful people, who fight when it is carefully explained to them what they are fighting for. When completely ex hausted he sat down on ground that had been drenched with mustard. Convalescent sergeants and corporals sitting around the ward with nothing to do would take pleas ure in worrying little Willy Bell. The cares of the day vanish with the first savage strike of a bluefish in the tide rip. Hooking one knee over the tiller of the little Sheilah, I can head toward home while filleting a couple of fish for dinner. See Sinus trouble Anxiety state, 123, 125-26 Appendicitis, 139, 177 Apprehension, feeling of, 121 Army of Occupation, 28 Arsenic poisoning, 212 Arterial hypertension, 122 Arteries, hardening of. See Hard ening of the arteries Arteriosclerosis, 2, 105, 107, 110, 112, 113, 116 Arthritis. Four, 28 Evans, Evan, 4, 18, 19, 20, 137 Exercise, in anti-obesity routine, 46, 69, 71, 104, 105, 110, 111-12, 116, 123, 130, 149 50, 192, 197; in treatment of arthritis, 81-82, 84-100 Exhaustion, sense of, 138, 139, 148, 194, 196-97, 210 Exhibitionism, 196 Eye redness, 139-40 False high blood pressure, 122 Farragut, Admiral David, 10 Fats, 114, 115, 203, 206 Fatty acids, 57, 58, 59 Feet, care of, 104-5. See also Frozen food; Primitive foods Food poisoning, 176, 213 Fordyce, John, 19 Foreign protein, 154, 160, 167, 168, 197; vaccinating with, 149, 151-54, 167 Friendly Arctic, The, 38 Frontal sinuses, 167 Frozen foods, 215-17 Fruits, 211, 231-32; in anti-obes ity routine, 150, 185, 191, 197 Gall bladder, 129, 131, 150, 188 Gall bladder dye test, 129, 130 Gallstones, 2, 77, 127-32, 188 Gangrene, diabetic, 102, 107, 108 Gastric irritability, 139 Gastric ulcer, 139 Gelatine, 205 Glandular fever, 140, 165 Glucose, 56 Glutamic acid, 205, 214 Gluttony, 103, 107 Glycogen, 56, 57, 58, 59 Glycolipides, 114 Godlowski, Z. See Poliomye litis Infectious hepatitis, 131, 140, 165 Influenza, epidemic, 28 Insomnia, 121 Insulin, 36, 57, 101, 103, 104, 106, 108 Intermittent claudication, 109 Internes, hospital, 5-6, 18-19, 82, 167, 174, 175 Intestinal irritability, 139 Janeway, Edward, 4 Jaundice, 127, 131, 165 Ketones, 57, 58, 59 Kidney disease, 114 Knee joints, exercise for arthritic, 100 Korean War, 26 Lamb chops, 224 Lamb stew, 222-23 Larkin, John, 18 Lecithin, 114 Leucorrhea, 139 Lewis, Thomas, 30 Life of the White Ant, The, 55 Lipides, 114 Liver, the, 58, 67, 131, 148, 150, 158-59, 166 Long Island College Hospital, 16 Low-calorie diets, 2, 32, 43, 49, 58-59, 192-93 Low-cholesterol diet, 114-15 Luer syringe, 151 Lumbago, 140 Lysine, 204, 205 MacArthur, Douglas, 117 MacKenzie, James, 30 Maeterlinck, Maurice, 55 Magnesium, 203 Malaria, 155, 164 Managerial sense, 117 Mass immunization, 163 Mastoiditis, 140, 155 Mastoids, 167 McCay, Winsor, 207 McClellan, Walter S. Six, 24 Rheumatic fever, 140, 155, 181 Rheumatoid arthritis, 84 Rice, 228-29 Ringworm. Louis encephalitis virus, 162 Salt, in anti-obesity routine, 68, 79, 104, 111, 124 Saturated fats, 115 Sauces, 225 Sausage, 223-24 Savenay, France, 22, 25 Scarlet fever, 14, 140 Scott, John, 13 Scratch tests, 142 Scurvy, 204 Sebaceous gland, 166 Security, longing for, 117 Sensitization, 135 Sherman, Essie, 4 Shingles, 139 Shock tissue, 137, 139, 166, 171, 181, 189 Shoes, 184 Shoulder joints, exercise for ar thritic, 88-89 Simple life, the, 218-35 Sinus trouble (antritis), 137,147 48, 167-70 Skin, vulnerable, 139, 148, 179 86 Skin testing, 137,142 Sleeping medicine, 109, 110 Sleeping sickness, 140 Slipped disc, 97 Small intestine, 171 Smallpox, 155 Sneezing, 139, 167 Snoring, 138, 139, 167, 195, 196, 200 Sodium propionate, 214 Soup, canned, 214-15 Sphenoids, 167 Spices, 229 Spinal curvature, 97 Starch, 57 Steaks, 224-25 Steam heat, 157 Stefansson, Vilhjalmur, 38-39, 40-41 Sterols, 114 Stigmata or degeneracy, 27 Stomach, 171-72 Stress. Department of Health and Human Services Suggested citation: Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. The transmission requirements are intended to improve the interoperability, or communication, of cancer registry data with other electronic record systems. Report Pilocytic/Juvenile astrocytomas; code the histology and behavior as 9421/3 iv. As of the 2018 data submission, cervical in situ carcinoma is no longer required for any diagnosis year. Sequence all cervix in situ cases in the 60-88 range regardless of diagnosis year. In the absence of documentation of stillbirth, abortion or fetal death, assume there was a live birth and report the case. Disease Regression When a reportable diagnosis is confirmed prior to birth and disease is not evident at birth due to regression, accession the case based on the pre-birth diagnosis. A clinical diagnosis may be recorded in the final diagnosis on the face sheet or other parts of the medical record. Use the casefinding lists to screen prospective cases and identify cancer cases for inclusion in the registry. It is important to include all casefinding sources when searching for reportable cases. Casefinding lists are intended for searching a variety of cases so as not to miss any reportable cases. Note: Suspicious cytology means any cytology report diagnosis that uses an ambiguous term, including ambiguous terms that are listed as reportable in this manual. If the physician is not available, the medical record, and any other pertinent reports. The CoC recognizes that not every registrar has access to the physician who diagnosed and/or staged the tumor, as a result, the Ambiguous Terminology lists continue to be used in CoC-accredited programs and maintained by CoC as "references of last resort. If any of the reportable ambiguous terms precede a word that is synonymous with an in situ or invasive tumor. Negative Example: the final diagnosis on the outpatient report reads: Rule out pancreatic cancer. Accession the case based on the reportable ambiguous term when there are reportable and non-reportable ambiguous terms in the medical record 1.